by Ming Gui, Change Maker

From the massive underrepresentation of females in video games to the sexualisation of female characters, video games have been responsible for promoting gender norms and stereotypes. Since we were young, we have seen female characters like Princess Peach and Zelda portrayed as damsels in distress, waiting around for a male character to rescue them.

So why these stereotypes are an issue, and what are their impact?

Firstly, it encourages negative attitude and beliefs

In games like Grand Theft Auto, Tomb Raider and Dead or Alive, female characters are shown as scantily-clad women with large breasts, an impossibly slim figure and a face that society would describe as beautiful or sexy. In fact, a study by Dill and Thill in 2005 found that 80% of video games include such portrayal of women. Female characters are also, more often than not, portrayed as weak, dependent or as damsels in distress.

In games like Grand Theft Auto, Tomb Raider and Dead or Alive, female characters are shown as scantily-clad women with large breasts, an impossibly slim figure and a face that society would describe as beautiful or sexy. In fact, a study by Dill and Thill in 2005 found that 80% of video games include such portrayal of women. Female characters are also, more often than not, portrayed as weak, dependent or as damsels in distress.

What kind of message would this send to the players? That girls should aim to achieve the body of, and dress just like, the female characters in order to be liked? Or that women are supposed to always wait around for a guy to rescue her?

How are you even supposed to fight enemies while dressed like that? I would be too busy pulling and adjusting that thin piece of cloth covering my important parts whenever I walked.

Secondly, it encourages tolerance and support for sexual harassment and rape

Research by Dill, Brown, and Collins found that long-term exposure to violent video games can lead to more tolerance towards sexual violence. One possible reason could be that because video games portray sexual harassment and rape as the norm, it is also seen as the norm by the player, even in real life. Sometimes, the game might even praise the player for using such violent means to progress through a mission.

This is further supported by a study done by Yao, Mahood, and Linz. Of the 74 males who were assigned to play either a sexually-explicit or non-sexually-explicit game, those who played a sexually-explicit game were more likely to view women as sex objects and display inappropriate behaviours towards them.

This is further supported by a study done by Yao, Mahood, and Linz. Of the 74 males who were assigned to play either a sexually-explicit or non-sexually-explicit game, those who played a sexually-explicit game were more likely to view women as sex objects and display inappropriate behaviours towards them.

Some may argue that men are equally objectified in video games because they are portrayed to be muscular, strong and impossibly well-built. However…

If we examine the traits given to female and male characters, we will notice that female characters are usually portrayed to have no other personality other than their big bust and beautiful figure. Whereas for male characters, they are usually portrayed as not just muscular, but strong, courageous and brave. There is a difference in the messages the game sends across to each gender. Being portrayed as nothing but a beautiful figure is not the same as being portrayed as a muscular and strong person. One is passive while the other is active.

As video game critique Jimquisition points out, there is a difference: Female characters are objectified while male characters are idealised.

As the video game industry is worth billions of dollars with millions of players, changes need to be made in the video game industry in order to further promote the cause of gender equality. If game producers were to be a little more mindful of the gender stereotypes they portray in their games, we will be one step closer to gender equality.

As a child, I remember that my favourite game is Super Mario. In the game, Princess Peach is always being kidnapped by the big bad guy Browser, and it is up to Mario and Luigi to save her. Because the characters are cartoons and I play as Mario, it does not have that much of an impact on my views of men and women. However, I recall finding myself wishing that I can play as Princess Peach instead, and have my own adventures to escape from Browser’s castle.

As I got older, the gaming world grew as well. I started playing a few MMORPGs. In these games, I noticed that female characters always have great clothes, really big busts and just look really pretty. I remember spending a lot of time customising my character. Before I knew it, I started wishing that I could look like them. I even started altering my appearance, and buying accessories that looks like the character’s. Looking back, it was the first time I actually took notice of my own appearance and started being self-conscious. It affected me slightly, as I fought to attain the unachievable beauty of my character, spending hours in front of my computer screen and visualising myself looking like my character.

As I got older, the gaming world grew as well. I started playing a few MMORPGs. In these games, I noticed that female characters always have great clothes, really big busts and just look really pretty. I remember spending a lot of time customising my character. Before I knew it, I started wishing that I could look like them. I even started altering my appearance, and buying accessories that looks like the character’s. Looking back, it was the first time I actually took notice of my own appearance and started being self-conscious. It affected me slightly, as I fought to attain the unachievable beauty of my character, spending hours in front of my computer screen and visualising myself looking like my character.

Now, as a young adult, I feel confident with my own looks. I now play games for the plot and storyline, not for the beauty of the characters. However, my story illustrates the impact that gaming has on young teenagers who are still learning to accept and love their own bodies.

As a hardcore female gamer, I would love to play a game where female characters are shown as brave warriors, but without being scantily-clad or sexualised. I would love to play a game where male characters are not always the aggressive one, and are capable of showing emotions.

I would love to play a game meant for everybody.

References:

Dill, K. E., Brown, B. P., & Collins, M. A. (2008). Effects of exposure to sex-stereotyped video game characters on tolerance of sexual harassment. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 44(5), 1402–1408. doi:10.1016/j.jesp.2008.06.002

Dill, K. E, & Thill, K. P. (2007). Video game characters and the socialization of gender roles: Young people’s perceptions mirror sexist media depictions. Sex Roles, 57, 851–864. doi:10.1007/s11199-007-9278-1

Yao, M. Z., Mahood, C., & Linz, D. (2009). Sexual priming, gender stereotyping, and likelihood to sexually harass: Examining the cognitive effects of playing a sexually-explicit video game. Sex Roles, 62(1-2), 77–88. doi: 10.1007/s11199-009-9695-4

About the Author: Min is a hardcore gamer with a Steam library loaded with games. She loves Skyrim, Two Worlds, GTA, Vampire: The Masquerade, Pokemon, Ace Attorney, Final Fantasy, and the list could stretch on for miles. She hopes to play more games that allows her to play as a strong female character.

Let’s first break down Arquette’s exact words to understand exactly why they were so controversial:

Let’s first break down Arquette’s exact words to understand exactly why they were so controversial:

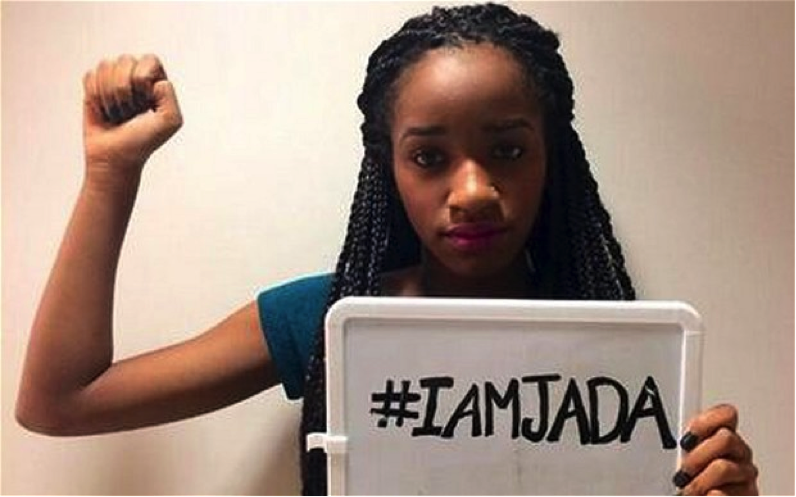

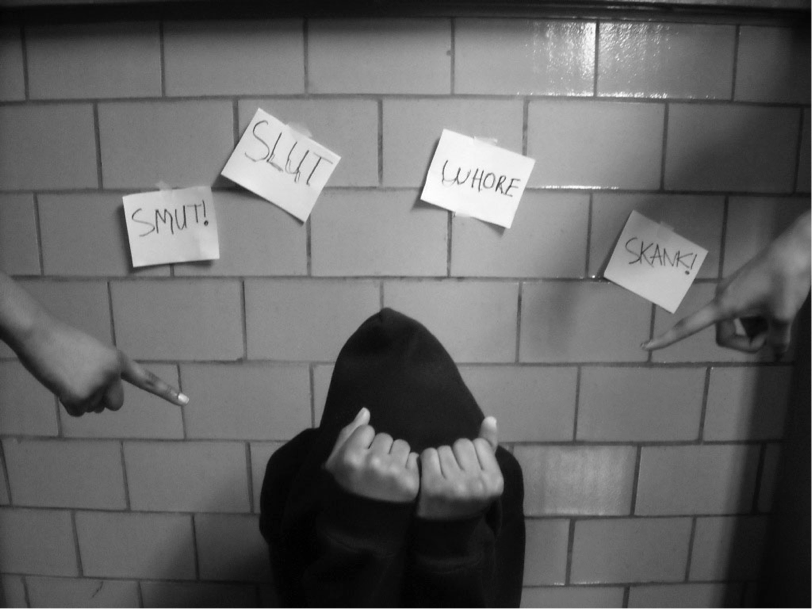

Increasingly, the proliferation of social media and the ability to hide behind anonymity have fuelled malicious attacks on individuals perceived as sexually promiscuous. In 2013, the hashtag #slanegirl was particularly infamous, as Twitter users collectively denounced a girl caught performing oral sex at a concert venue, with some even going to the extent of publishing her full name and age on online public spaces. More recently, schools in USA are facing protests after humiliating students who were perceived to be inappropriately dressed by forcing them to wear loose fitting “shame suits”. Such behavior, however, irresponsibly perpetuates the damaging outlook that victims are responsible for their own plight, while removing responsibility from perpetrators.

Increasingly, the proliferation of social media and the ability to hide behind anonymity have fuelled malicious attacks on individuals perceived as sexually promiscuous. In 2013, the hashtag #slanegirl was particularly infamous, as Twitter users collectively denounced a girl caught performing oral sex at a concert venue, with some even going to the extent of publishing her full name and age on online public spaces. More recently, schools in USA are facing protests after humiliating students who were perceived to be inappropriately dressed by forcing them to wear loose fitting “shame suits”. Such behavior, however, irresponsibly perpetuates the damaging outlook that victims are responsible for their own plight, while removing responsibility from perpetrators.