By Natasha Sadiq & Tan Jing Min

“How long does it take for an Indian woman to pass motion?”

“How long?”

“9 months”

Cackles of laughter ensue. I look around the group of friends encircling me. I seem to be the only person who didn’t find the joke funny.

I’m going to go out on a limb here (I might be completely wrong) and guess that it’s because I’m the only person of Indian descent. I tried hard to conceal the indignation coalescing on my face.

I failed. I suppose they couldn’t miss my suddenly darkened face.

“But it’s just a joke, don’t be so sensitive la.”

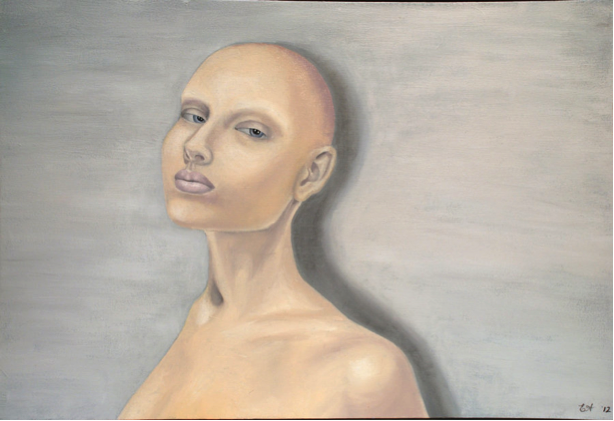

And they were right: it was just a joke. But the jokes we tell speak volumes about our subliminal racial biases and standards of beauty. Colour is the subject of much banter among youths and even some circles of adults especially in multiracial Singapore, but the light-hearted irreverence belies more insidious undertones: body shaming and body image issues.

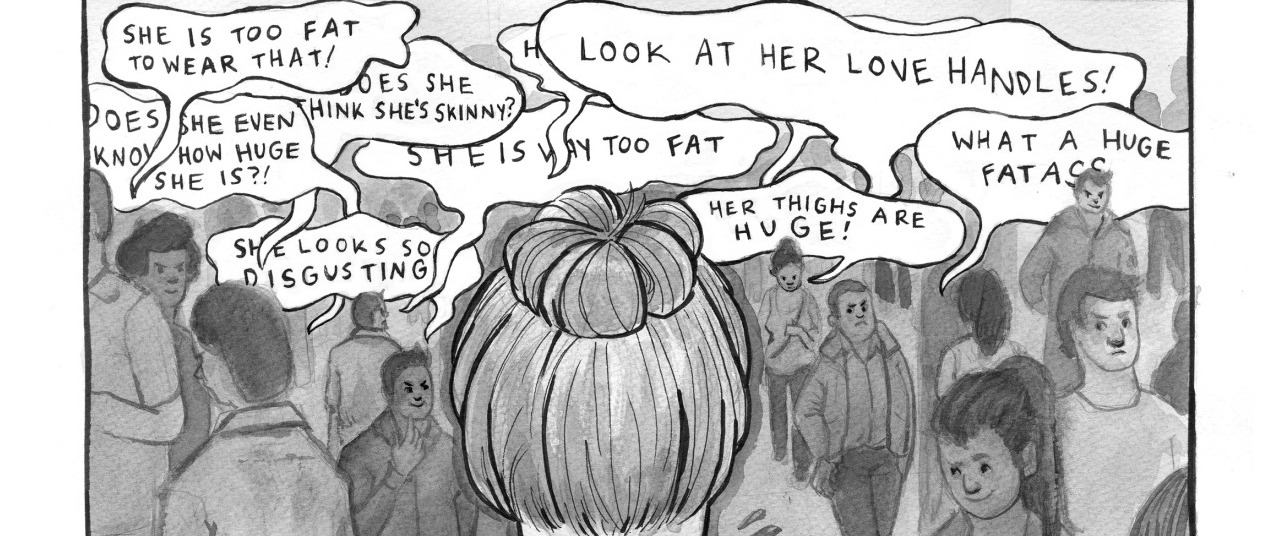

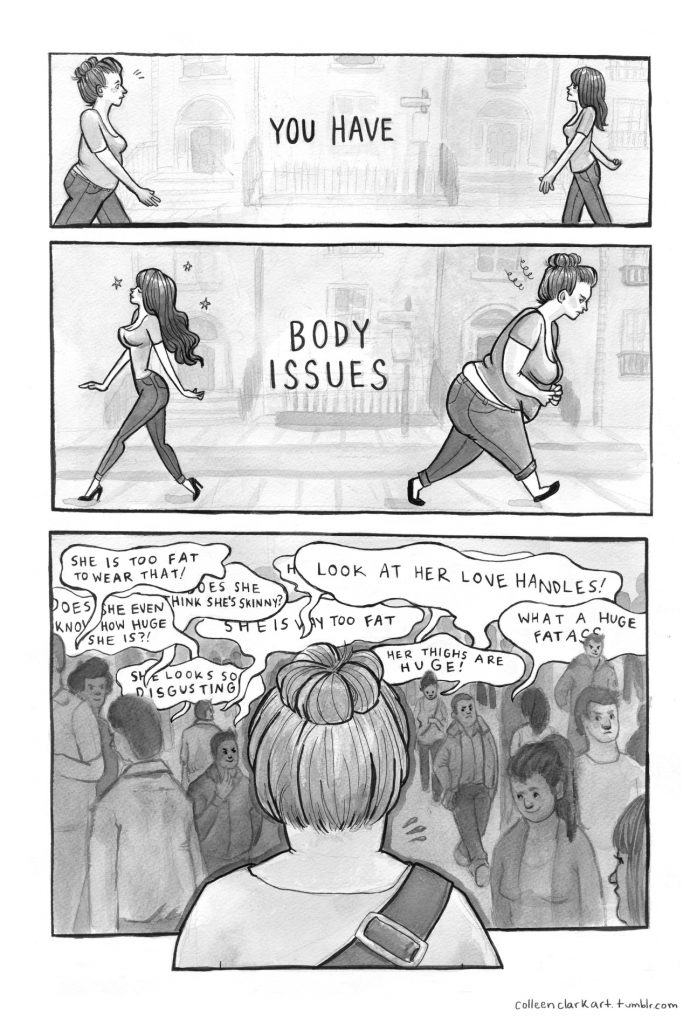

Body shaming is the practice of making mortifying and demeaning remarks about a person’s body size, weight, or appearance. The prevalence of body shaming in societies should not be trivialised – anxieties about one’s beauty and appearance are rising exponentially.

According to the Dove Global Beauty and Confidence Report, Dove’s largest-ever study on women’s perceptions of beauty, research shows that women’s level of body confidence is at an all-time low. The study, which involved interviews with 10,500 women across 13 different countries, showed that a large majority of women struggle with body image issues.

The study also showed that body image issues are not confined to a mere lack of confidence and physical insecurities. These issues do pose consequences on a much broader and larger scale. For example, the study showed that about 85 per cent of all women and 79 per cent of girls admitted that they choose to absent themselves from important life events when they do not feel confident about their appearance. Additionally, 9 out of 10 women skip meals and compromise their health when they feel insecure about their bodies.

The problem of body shaming can also manifest in tangible third-party harm: a study by the Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) showed that bullying in Singapore is worryingly high compared to other countries – the third highest, to be exact. 18.3 per cent of students experience ridicule a few times a month. Spreading of rumours, being left out, and having things taken away from them were among the other forms of bullying cited by students.

This is telling of a mindset internalised from early childhood: we are entitled to judge others, and ostracise others if they fail to meet the mark.

In Singapore, casual racist remarks about one’s appearances may also constitute body shaming. One can even argue that these remarks are more damaging to a person’s self-esteem because changing one’s race or skin colour would be arguably more difficult than altering one’s weight. Here, body shaming is a reality not merely for girls and women, but for boys and men as well.

Indeed, body shaming and racial stereotypes share a symbiotic relationship. Racial stereotypes and colourism contribute to a culture of body shaming (and vice versa) when people associate a certain race with certain physical characteristics, and then conceive of a narrow standard of beauty based on certain “undesirable” traits found in one’s race or physical appearance.

One example of this is when we attribute certain physical traits like fatness, darker skin tones and even unkempt hair to certain races, consequently branding them “lazy” or “unprofessional”.

What we need to be more aware of is the fact that individualised instances of casual racism have the potential to affect how we perceive broader social groups and communities. Here, something as personalised and singular as casual racism helps build the foundation for larger issues of social prejudice.

Because skin colour can be such a visceral reminder of how one individual differs from another, it is especially important that we take heed of our latent biases. The issue of race regularly arises in national discourse for good reason–from racial politics to majority privilege, it is clear that while Singapore embraces diversity, it also poses a constant potential source of tension.

Whether we are concerned with seemingly superficial issues like physical appearances or those that entail greater social implications like race, we need to understand that they are all connected by threads of influence. The seemingly light-hearted jokes about race we pass around as pleasantries carry more poison in its arsenal than we think.

About the authors:

Natasha graduated from NUS with a degree in Political Science and dislikes empty niceties. She is currently looking for her job. Please inform her if you find it.

Jing Min is waiting to begin reading Law at Cambridge University, but looks like she could be starting primary school. She tries to use this to her advantage (with little success).

Featured image by Natalie Nourigat.