by Charmaine Teh, Change Maker

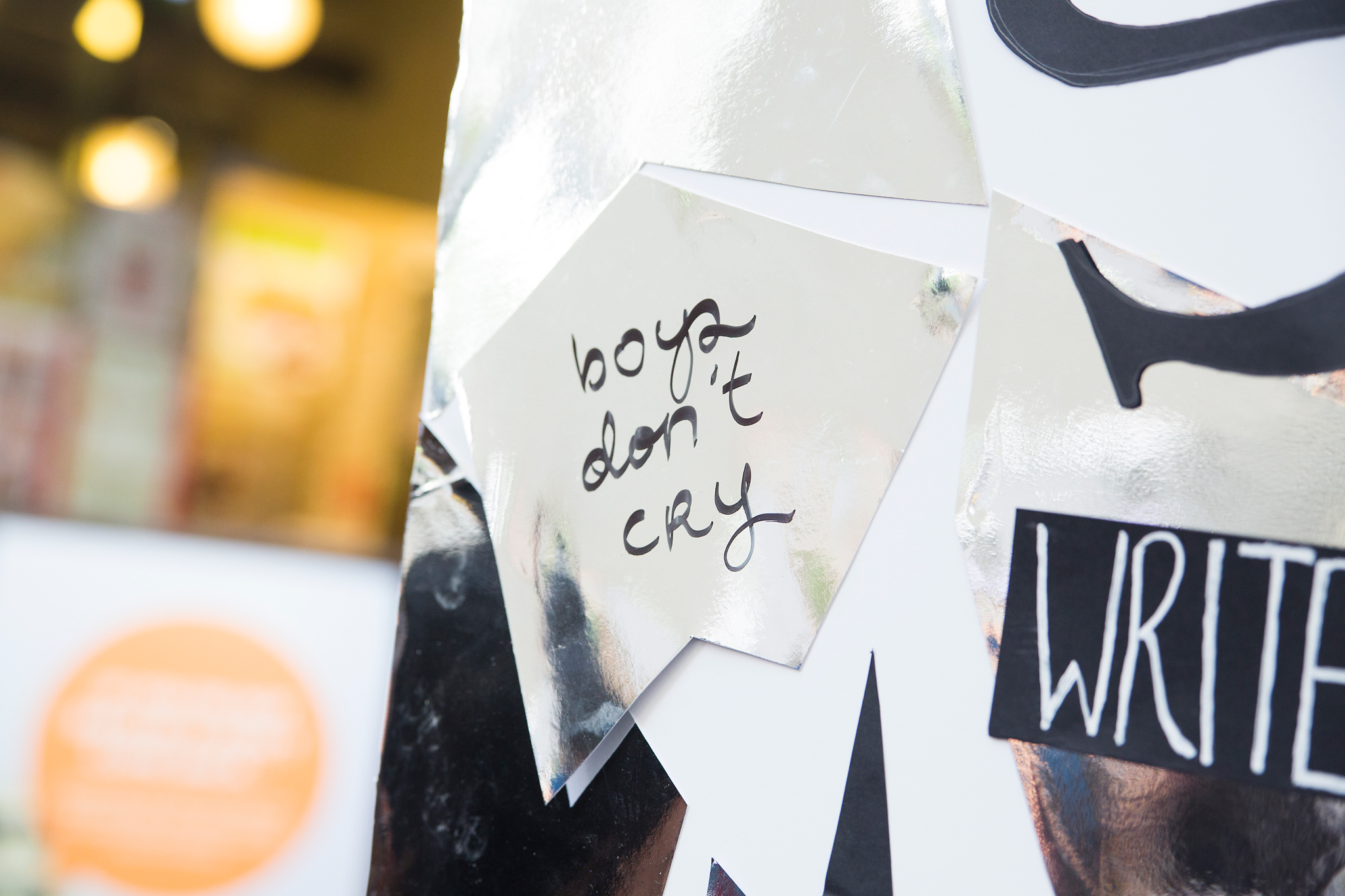

We live in a society where our appearances are constantly under close scrutiny. Due to rigid societal standards, picking on someone for their weight, whether they are plus size or skinny, is common. The media portrays the perfect female body as a skinny physique with killer abs or a flat tummy with the infamous thigh gap, and for the guys, a chiseled, muscular body. This sends the message that these features would automatically make you happier, more popular and more desirable.

We live in a society where our appearances are constantly under close scrutiny. Due to rigid societal standards, picking on someone for their weight, whether they are plus size or skinny, is common. The media portrays the perfect female body as a skinny physique with killer abs or a flat tummy with the infamous thigh gap, and for the guys, a chiseled, muscular body. This sends the message that these features would automatically make you happier, more popular and more desirable.

Beauty is constantly being redefined. Currently, the media equates skinny to beautiful; and if you aren’t skinny, you can’t possibly comply with society’s standards of beauty. Anything other than that, you are not fitting in. It has become so ingrained in us that we may find ourselves alienating or disliking a person simply because he or she is fat. And if you are not skinny, you may be called names like ‘fat’ and ‘ugly’, which are meant as insults.

I used to be a victim of ridicule because I was chubby and stood out from my group of friends like a sore thumb. I had thighs that rubbed together when I walked and a tummy that bulged out when I sat down. Someone thought I was “ugly”, and saw fit to ridicule me. I was constantly humiliated for my size and it was a huge blow to my self-esteem. Even though I weighed 51kg standing at 1.57m, I started feeling ugly and believed that I was severely overweight. I turned to starvation by surviving on only one meal per day. On days when I felt ugly and fat, I would binge on food and then exercise excessively to account for the calories I had consumed. I became increasingly self-conscious about my body. I would never leave home in clothes that could not conceal the extra bulges I was trying to hide.

Although I was never medically diagnosed with any eating disorders, it did not mean that I was not harming my body. Within a month, I became obsessed with losing weight. I ate nothing but a plain toast for breakfast and drank water to stave off my hunger for the rest of the day. I felt weak all over but I saw it as something I had to overcome in order to lose weight. To make things worse, I was participating in intensive trainings for my extracurricular activity thrice a week. I was constantly hungry after training sessions but reminded myself that the only way to be skinny was to stick to my strict regime of excessive dieting and exercising.

Why did I allow my beauty to be defined by anyone else but myself? I thought that by being skinnier, I would become a happier and more beautiful person but I only felt depressed and disgusted at myself all the time. I had forgotten that I am an unique individual who deserves to feel beautiful because I am born beautiful, regardless of how I look.

Why did I allow my beauty to be defined by anyone else but myself? I thought that by being skinnier, I would become a happier and more beautiful person but I only felt depressed and disgusted at myself all the time. I had forgotten that I am an unique individual who deserves to feel beautiful because I am born beautiful, regardless of how I look.

What I am trying to say is that no one should feel ashamed of their body simply because they are not as skinny or muscular. Everyone should be able to feel comfortable in their own skin even if they do not conform to societal standards of beauty.

Beauty comes in all shapes and sizes, not just the body type the media portrays. Therefore, my message to anyone out there who feels insecure about their body is that the next time you feel inferior because you do not have rock-solid muscles or a thigh gap, just remember that your body is unique and that you are beautiful. Don’t let the media or society tell you otherwise.

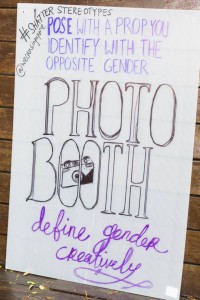

About the Author: Charmaine is a final year student at Ngee Ann Polytechnic pursuing Psychology Studies. Her interest in gender equality first sparked when she mentioned that her ex-netball coach was a male and someone had exclaimed ‘Guys can play netball too?’ She holds strong to the belief that no matter how big or small a change is, it is still something significant and thus we should never stop trying to advocate change in the society.

About the Author: Charmaine is a final year student at Ngee Ann Polytechnic pursuing Psychology Studies. Her interest in gender equality first sparked when she mentioned that her ex-netball coach was a male and someone had exclaimed ‘Guys can play netball too?’ She holds strong to the belief that no matter how big or small a change is, it is still something significant and thus we should never stop trying to advocate change in the society.