Written by Kimberly J, Change Maker

I would like to start off this article with a disclaimer: I am not advocating the comparison of women. People should be allowed to live their lives in their own ways, different as they may be. However, I would like to use the differing treatments of the two women in question to explore a strange and somewhat distressing phenomenon in the pop music industry.

Taylor Swift is often mocked and disparaged by men and women alike for her lyrics about her romantic  exploits. I will not expound on the insults I have heard about her (“ew, you like Taylor Swift?”), nor will I attempt to describe all the face scrunches I see when I say her name (A one-sided affair, with the cheekbone raised so high that a part of the left eye gets obscured from view in disgust). I will, however, point out that it seems socially acceptable to abuse her for her adventures in dating. This seems to stand in spite of the seemingly contradictory praise of male artistes who write songs about their exes or love interests.

exploits. I will not expound on the insults I have heard about her (“ew, you like Taylor Swift?”), nor will I attempt to describe all the face scrunches I see when I say her name (A one-sided affair, with the cheekbone raised so high that a part of the left eye gets obscured from view in disgust). I will, however, point out that it seems socially acceptable to abuse her for her adventures in dating. This seems to stand in spite of the seemingly contradictory praise of male artistes who write songs about their exes or love interests.

It is true that Swift’s older lyrics focused on hate for her exes, and often promoted putting other women down. However, her recent open rallying for the cause has been raising much awareness amongst her fans. Her admission of her previous mistakes regarding feminism is admirable. Her relentless insistence on talking about it, her determination to call out the problematic qualities of the media that facilitated her fame in the first place – these little things she has done look worthy of some impressed raised eyebrows, yet are constantly swept under the rug in exchange for more talk of her exes.

On the flip side, Meghan Trainor has been hailed as a feminist, ever since her catchy song All About that Bass, attracting a lot of praise for the seeming body positivity, and one too many treble/trouble puns.

However, Trainor is also known for refusing to identify as a feminist. Her misguided ideas about feminism seem to tie in with the accusations of body-shaming (as in the lyrics “skinny bitches”), and the promotion of the idea that a larger body is only acceptable because men like it. Trainor doesn’t seem to be a feminist, yet much of the approval she receives tends to stem from body positivity and feminism. She is profiting from the very cause that she rejects.

However, Trainor is also known for refusing to identify as a feminist. Her misguided ideas about feminism seem to tie in with the accusations of body-shaming (as in the lyrics “skinny bitches”), and the promotion of the idea that a larger body is only acceptable because men like it. Trainor doesn’t seem to be a feminist, yet much of the approval she receives tends to stem from body positivity and feminism. She is profiting from the very cause that she rejects.

Audiences seem to have mismatched attitudes about Swift and Trainor, and it appears to stem largely from Swift’s illustrious and public dating history.

Swift’s nods to feminism are often buried under a layer of subtle Grade A slut shaming. Her entire career is shaped almost entirely by the people she has dated. Sure, she has deviated from that lately, but it doesn’t change the fact that she started out as a young girl with a penchant for romance and crying on musical instruments. Yet the media thinks it appropriate to package her career – this adolescent naïve 16-year-old girl’s career – as a train wreck of failed relationships, casually ignoring the very point of dating. Trainor, on the other hand, is the same misguided young woman who has much to learn, yet is commended for her problematic journey of body positivity.

This is by no means a competition (though the music industry might beg to differ), but a display of the gross double standard that many of the audience adopt. Feminism seems only applicable to certain people when it suits their needs; when its name rears its ugly head fighting for the rights they take for granted, they fall back into the protective bubble of social acceptability. It doesn’t matter to them if the feminism they like comes at the expense of others. As long as the word “feminist” and its underwear-tossing, fire-hazardous connotations are avoided, the party can continue.

This is by no means a competition (though the music industry might beg to differ), but a display of the gross double standard that many of the audience adopt. Feminism seems only applicable to certain people when it suits their needs; when its name rears its ugly head fighting for the rights they take for granted, they fall back into the protective bubble of social acceptability. It doesn’t matter to them if the feminism they like comes at the expense of others. As long as the word “feminist” and its underwear-tossing, fire-hazardous connotations are avoided, the party can continue.

At this point I feel obliged to announce that I am perfectly aware of the fact that I am talking of women who are incredibly privileged. The collection of the following traits: white, American, and earning a substantial amount of money from their careers seems like an invitation to the very same criticisms faced by first wave feminism. I acknowledge the limitations to this exploration, though the basis of my observations stand.

I implore the consumers of pop music to think twice before automatically dismissing Taylor Swift or embracing Meghan Trainor. You might dislike/like her songs, or you might dislike/like her, but I would examine why. Pop culture always seems like the background hum of our lives, but maybe paying attention to it and taking it a little more seriously can reveal a lot about internalised slut shaming, and finding that there is so much to unlearn.

About the author: Kimberly is a somewhat ambitious NUS undergraduate who has always dreamed of writing her own About the Author section. She retains much hope for eventual equality, and is willing to fight the currents to get there.

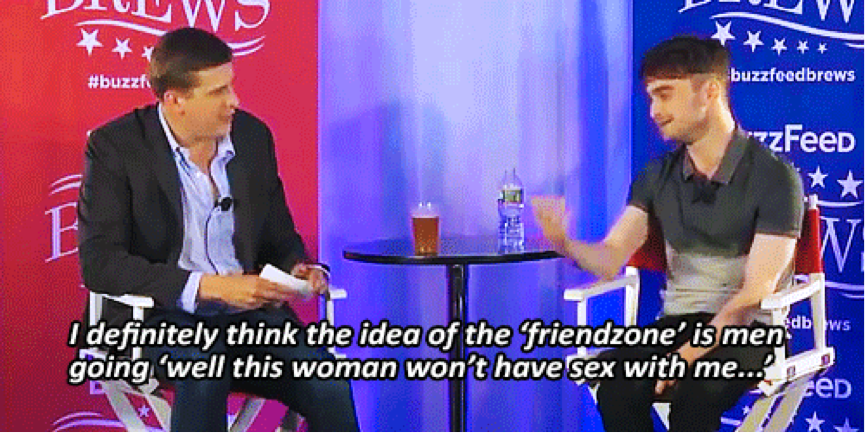

More worryingly, however, the strong need for men to shame women into having relationships with them seems to stem from some kind of patriarchal expectation. There is a strong pressure from Singaporean families to get married and have children, which explains a desire to have a romantic relationship in order to prove their relevance and membership in society. For many people, a relationship is seen as a mark of success, a flag of victory. What many don’t see is that this illusion of the perfect relationship is not essential in one’s emotional and psychological well-being. The Friend Zone can be seen as a harmful and sexist attack on women’s rights, but it can also be the product of incessant pressures to be “with someone” and harsh patriarchal rules.

More worryingly, however, the strong need for men to shame women into having relationships with them seems to stem from some kind of patriarchal expectation. There is a strong pressure from Singaporean families to get married and have children, which explains a desire to have a romantic relationship in order to prove their relevance and membership in society. For many people, a relationship is seen as a mark of success, a flag of victory. What many don’t see is that this illusion of the perfect relationship is not essential in one’s emotional and psychological well-being. The Friend Zone can be seen as a harmful and sexist attack on women’s rights, but it can also be the product of incessant pressures to be “with someone” and harsh patriarchal rules.

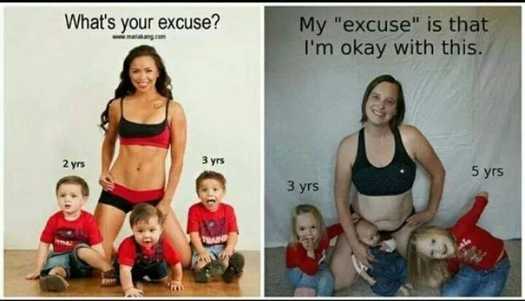

Does this sound familiar? These statements are commonly directed towards fat people in attempts to control or police their bodies. Fat-shaming is the act of discriminating against a person because of their weight, and often involves publicly policing fat people’s appearance, behaviour, and attitude. We’ve all likely experienced fat-shaming as a victim, perpetrator or as both.

Does this sound familiar? These statements are commonly directed towards fat people in attempts to control or police their bodies. Fat-shaming is the act of discriminating against a person because of their weight, and often involves publicly policing fat people’s appearance, behaviour, and attitude. We’ve all likely experienced fat-shaming as a victim, perpetrator or as both. How is the policing of women’s body size misogynistic?

How is the policing of women’s body size misogynistic?

As I got older, the gaming world grew as well. I started playing a few MMORPGs. In these games, I noticed that female characters always have great clothes, really big busts and just look really pretty. I remember spending a lot of time customising my character. Before I knew it, I started wishing that I could look like them. I even started altering my appearance, and buying accessories that looks like the character’s. Looking back, it was the first time I actually took notice of my own appearance and started being self-conscious. It affected me slightly, as I fought to attain the unachievable beauty of my character, spending hours in front of my computer screen and visualising myself looking like my character.

As I got older, the gaming world grew as well. I started playing a few MMORPGs. In these games, I noticed that female characters always have great clothes, really big busts and just look really pretty. I remember spending a lot of time customising my character. Before I knew it, I started wishing that I could look like them. I even started altering my appearance, and buying accessories that looks like the character’s. Looking back, it was the first time I actually took notice of my own appearance and started being self-conscious. It affected me slightly, as I fought to attain the unachievable beauty of my character, spending hours in front of my computer screen and visualising myself looking like my character.