by Kimberly Jow, Change Maker

You hear stories of the Friend Zone all the time. Guy is friends with girl, guy falls for girl, he is rejected and they remain friends, though he is often resentful and upset at this turn of events. The story follows Guy and his adventures in dealing with heartbreak, and often a happy ending is when he finally manages to get the girl. This sounds like a great movie pitch, and I would send it into Hollywood, who is on my speed dial, but it’s already been done.

You hear stories of the Friend Zone all the time. Guy is friends with girl, guy falls for girl, he is rejected and they remain friends, though he is often resentful and upset at this turn of events. The story follows Guy and his adventures in dealing with heartbreak, and often a happy ending is when he finally manages to get the girl. This sounds like a great movie pitch, and I would send it into Hollywood, who is on my speed dial, but it’s already been done.

The pity attached to the phrase “the Friend Zone” is automatic; the man’s rejected advances are to be mourned, and the girl is immediately at fault. Her friendship is taken as a consolation prize, as a hurtful and unintelligent thing to offer in response to a Nice Guy who just wants to ask her out. Her friendship is not enough, and it is laughable that she thinks of him as “just” a good friend. She is seen to be blind, to be picky, and to have terrible taste in men.

I have heard many people say that the Friend Zone is without negative connotation. The “women who put them in the friend zone” is merely a category of women who have rejected their romances and now are friends. I don’t think that holds true. First off, the specificity of this category is problematic. Is a woman’s friendship after a rejection different from  normal friendships? If there were no negative connotations, why does it have to be in this special category of friendships? It almost seems as if the Friend Zone is an excuse to shame those women by putting them in a box and giving them a generalised name, attached to a series of traits they are expected to have.

normal friendships? If there were no negative connotations, why does it have to be in this special category of friendships? It almost seems as if the Friend Zone is an excuse to shame those women by putting them in a box and giving them a generalised name, attached to a series of traits they are expected to have.

Secondly, the fact that the phrase “the friend zone” mostly comes in a sentence like “Amy put me in the friend zone” suggests a fair amount of blame. Despite the fact that a person’s liking for Amy was unrequited, she is still the one playing the active role in “putting” him in this zone. You don’t hear people say, “I put myself in the friend zone with Amy”, because Hypothetical Amy is the one perceived to be at fault in this situation.

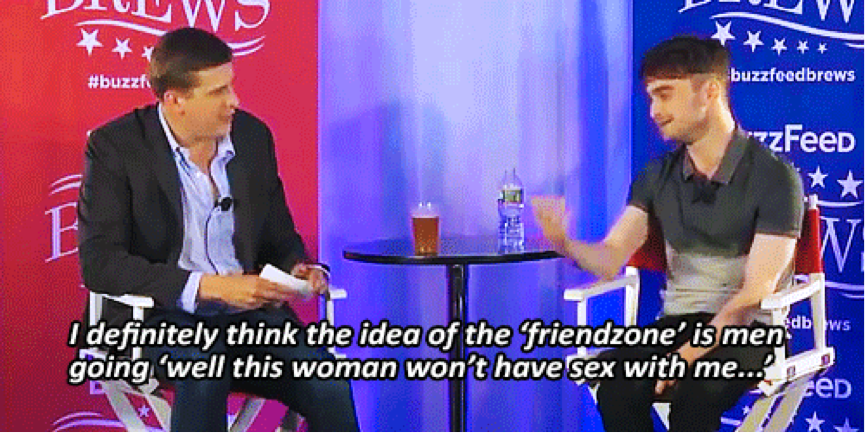

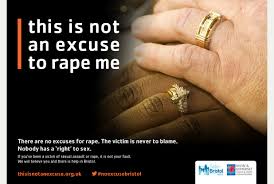

My main question would be, “Why?”. What is the purpose of this specificity, of this blame? I am not denying that having one’s affections rejected is painful, but the whole Friend Zone seems like one huge guilt trip. One feels entitled to a woman, and uses the all-mighty Friend Zone to shame her for exercising her right to choose. It’s sexist, and also heteronormative. One assumes that a man who has a female friend automatically wants to have a romantic relationship with her. Assuming otherwise is an insult to his masculinity, and it assumes his heterosexuality.

More worryingly, however, the strong need for men to shame women into having relationships with them seems to stem from some kind of patriarchal expectation. There is a strong pressure from Singaporean families to get married and have children, which explains a desire to have a romantic relationship in order to prove their relevance and membership in society. For many people, a relationship is seen as a mark of success, a flag of victory. What many don’t see is that this illusion of the perfect relationship is not essential in one’s emotional and psychological well-being. The Friend Zone can be seen as a harmful and sexist attack on women’s rights, but it can also be the product of incessant pressures to be “with someone” and harsh patriarchal rules.

More worryingly, however, the strong need for men to shame women into having relationships with them seems to stem from some kind of patriarchal expectation. There is a strong pressure from Singaporean families to get married and have children, which explains a desire to have a romantic relationship in order to prove their relevance and membership in society. For many people, a relationship is seen as a mark of success, a flag of victory. What many don’t see is that this illusion of the perfect relationship is not essential in one’s emotional and psychological well-being. The Friend Zone can be seen as a harmful and sexist attack on women’s rights, but it can also be the product of incessant pressures to be “with someone” and harsh patriarchal rules.

I cannot pretend to be able to solve this deeply complex issue. I acknowledge its tangled and deeply seated place in the large mass of sexism, and realise that my solutions could only scratch the surface. This will not stop me from trying. It is time we see a relationship for what it is – two people liking each other and both getting what they want from it, instead of an item on a checklist to be a functioning member of society. It is time that we fully understand the term “Friend Zone” in all its harmfulness, and stop using it in day-to-day life. And maybe it is time to admit that our society has exaggerated the healing properties of a relationship, and reassure ourselves that it is fine to get into relationships only when we are ready, instead of using harmful tools to get our way.

About the Author: Kimberly is a somewhat ambitious NUS undergraduate who has always dreamed of writing her own About the Author section. She retains much hope for eventual equality, and is willing to fight the currents to get there.

Let’s first break down Arquette’s exact words to understand exactly why they were so controversial:

Let’s first break down Arquette’s exact words to understand exactly why they were so controversial: