By Louise Low, Change Maker

“You would look so much better if you lost all that weight!”

“Wah! You still want to eat so much!”

“She shouldn’t be wearing that – she’s too fat.”

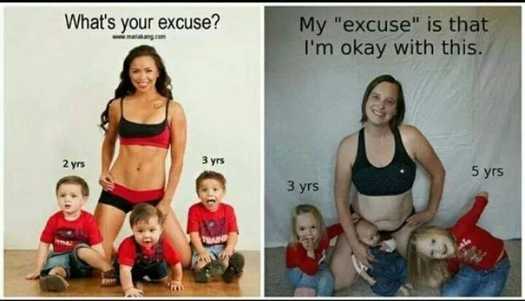

Does this sound familiar? These statements are commonly directed towards fat people in attempts to control or police their bodies. Fat-shaming is the act of discriminating against a person because of their weight, and often involves publicly policing fat people’s appearance, behaviour, and attitude. We’ve all likely experienced fat-shaming as a victim, perpetrator or as both.

Does this sound familiar? These statements are commonly directed towards fat people in attempts to control or police their bodies. Fat-shaming is the act of discriminating against a person because of their weight, and often involves publicly policing fat people’s appearance, behaviour, and attitude. We’ve all likely experienced fat-shaming as a victim, perpetrator or as both.

In societies like Singapore, many social factors combine to produce a general disapproval of larger bodies. Individuals feel entitled to police fat individuals – condemning their diet and attire, among other lifestyle choices, and sometimes openly disparaging them. It can be directed towards celebrities, strangers, friends, and children. People whom feel judged for their size often in turn internalise such attitudes and discriminate against other fat people. People of any gender may be subject to such treatment, though one’s age, race and environment among several varying factors affect their experience of fat shaming. This article focuses on the policing of women with fat bodies, its underlying misogynist roots, and its harms.

How do people police fat bodies?

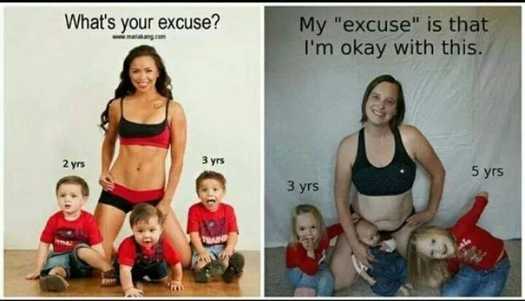

The intolerance of fat women’s bodies and the denial of their autonomy manifests itself in various forms. People hold fat women to certain expectations; in terms of behaviour, they are judged for what they eat, their physical activity, and their attire. For instance, fashion magazines or well-meaning friends or family might tell a fat person how to dress to appear slimmer, and deem certain articles of clothing unflattering or only meant for thinner frames; fat people, women especially, thus have an imposed limitation on their choice of clothing. In this manner, the fat individual’s attire is policed.

In terms of attitude, they are expected to be apologetic, self-conscious, and uncomfortable with their bodies, and to want to “remedy” their “problem”. They are obliged to feel responsible for the perceived unhealthy and unlikeable state of their bodies. I recall a joke on ‘The Noose’ in which a character proclaimed, to combat inappropriate attire, that uniforms should be imposed on polytechnics, “but not the sleeveless kind, like SCGS, because some of the girls’ arms are very fat.” Incidentally, I was studying at said school and wore an uncomfortable jacket everywhere out of insecurity – which was funnily affirmed by this aforementioned joke. Even though it might be done in jest, the constant and cumulative rejection and ridicule of large bodies has real impact on the self-esteem of individuals, particularly young women.

Why is it harmful?

Why is it harmful?

The policing of fat bodies compromises an individual’s physical and mental health. Studies have proven that fat-shaming is not only unhelpful in losing weight, but also exacerbates weight gain. It may also lead to body image issues, to which young girls are very susceptible, potentially causing mental illnesses like depression and anxiety, as well as eating disorders. A person pressured into losing weight via fat-shaming is not necessarily healthier, and may in fact hold misinformed ideas on health.

Decreased confidence and poor self-esteem could also affect a person’s choices and behaviour, forcing them to limit what they can or cannot do, and make decisions out of fear. They may also deem themselves unworthy of things such as love, from others or themselves. This belief may affect fat individuals too; it is a result of, and worsens how society deems fat people less deserving.

Besides compromising their health, the act of fat-shaming dehumanises fat people. I realised even accomplished women were subjected to discomfort and policed their own bodies when a highly skilled, experienced, and knowledgeable university professor would make self-depreciating jokes about her weight during lectures. Policing fat bodies dehumanises fat people, and may mislead some, including fat people themselves, to believe that it is a definitive and shameful aspect of their identity, regardless of their character and personal achievements.

How is the policing of women’s body size misogynistic?

How is the policing of women’s body size misogynistic?

“Misogyny” refers to the exhibition of hatred towards, or the mistreatment of, women. The policing of plus-sized women’s bodies are inextricably linked to and rooted in misogyny. The main reasons for fat-intolerance are male-centric views on female attractiveness and mainstream beauty standards. Take a walk down Orchard Road, and you’ll easily spot fashion advertisements featuring women of similar, slender build. (Another disturbing pattern you can observe is that a disproportionately large majority of the female models we see in beauty advertisements here are Caucasian or East Asian. This of course reveals not only the mainstream discrimination of women’s beauty by body types, but by race as well. Beauty standards are very often racialized, and this also stems from patriarchal systems as well as the objectification of women who are ethnic minorities, and is an issue that warrants its own discussion.)

Conversely, fat bodies receive negative media portrayal, and are regarded as a problem that needs to be fixed – women are bombarded daily with advertisements for weight loss treatments. They send a clear message as to what society deems acceptable – a narrow range of body types that excludes fat bodies. A more disturbing connotation, that is not always acknowledged, is that women’s bodies are not their own, but subject to male approval, and women are thus obliged to change their bodies to fit male standards.

Although there exist supposed counter-movements that praise “curvy” women and claim to inspire body positivity, they are unhelpful when acceptance for fatness is centred on it being more appealing to men, while rejecting smaller bodies. For example, ‘All About That Bass’ relies on lyrics that supposedly celebrate fat women by putting down thin women – “You know I won’t be no stick-figure, silicone Barbie doll” – even though body positivity is about acceptance of all bodies, and claiming that the former is more attractive to men – “boys they like a little more booty to hold at night”. This merely shifts sexual objectification from one body type to another, and personally, does not empower me as a plus-size woman. Women are not in competition with each other for male approval; no one body type should be deemed inferior to the other, by men. People should acknowledge women’s autonomy over their own bodies, instead of viewing “beauty” as something bestowed upon them by men.

Internalizing negative portrayals leads to anxieties regarding one’s own body, and leads to the judgement of others as well. A person with body image issues as a result of the policing of their bodies may apply unrealistic expectations upon themselves, and project such negative and unhealthy expectations onto others. This results in a collective condemnation of fat women, the root of which is negative stereotyping and gender expectations.

It is time to let go of the misconception that fat people are obliged to feel apologetic about themselves, and to stop the normalizing of harmful, sexist condemnation of fat women.

About the author: Louise is a feminist and an undergraduate at the National University of Singapore. Her most despised TV/movie trope is the one where a self-loathing plus-sized or otherwise supposedly unattractive female character learns to love herself through (or even worse: loses weight for) a romantic relationship with a male character.

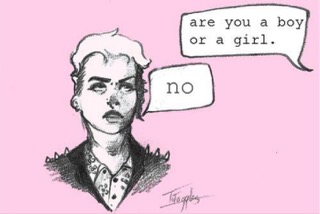

Being a man has been a complicated experience for me. I am a genderqueer person in a body that very much looks like a man’s. But I am not, and will never be a man, and it’s not for a lack of people trying to teach me how to be one.

Being a man has been a complicated experience for me. I am a genderqueer person in a body that very much looks like a man’s. But I am not, and will never be a man, and it’s not for a lack of people trying to teach me how to be one. I have not yet figured out how to look less like a man. On certain days when I’m feeling particularly dysphoric, every assumption that I’m a man makes my insides squirm. On other days the same assumptions simply bounce off my belly, leaving nary a mark. Most of the time, I find myself drawing a box labelled “Other” under the Gender section on some form. When neither box fits, you can only make your own. In spite of everything, these few months after my coming out as a genderqueer person has been so much more liberating than the years I spent being a man.

I have not yet figured out how to look less like a man. On certain days when I’m feeling particularly dysphoric, every assumption that I’m a man makes my insides squirm. On other days the same assumptions simply bounce off my belly, leaving nary a mark. Most of the time, I find myself drawing a box labelled “Other” under the Gender section on some form. When neither box fits, you can only make your own. In spite of everything, these few months after my coming out as a genderqueer person has been so much more liberating than the years I spent being a man.

You do not often see girls in the computer science track and the unspoken thought is that we are just less good at it: there are very few of us and we perform worse than our male counterparts. Hence, whenever we were in class, or during examinations, I felt like I had to prove that I did not fit the stereotype. I wanted to demonstrate that girls do not suck at coding. If I did badly, people would have one more reason to accept the stereotype as truth. In a way, I felt like I was representing my whole gender, not only myself.

You do not often see girls in the computer science track and the unspoken thought is that we are just less good at it: there are very few of us and we perform worse than our male counterparts. Hence, whenever we were in class, or during examinations, I felt like I had to prove that I did not fit the stereotype. I wanted to demonstrate that girls do not suck at coding. If I did badly, people would have one more reason to accept the stereotype as truth. In a way, I felt like I was representing my whole gender, not only myself.

Huang Yuzhu, played by Joanne Peh, is a young girl born into an affluent family. She is kind, helpful, bubbly, and generally a pretty nice person.

Huang Yuzhu, played by Joanne Peh, is a young girl born into an affluent family. She is kind, helpful, bubbly, and generally a pretty nice person. Clearly, local media has developed the very, very problematic habit of using rape as an easy and convenient plot device. And even more clearly, this has to stop.

Clearly, local media has developed the very, very problematic habit of using rape as an easy and convenient plot device. And even more clearly, this has to stop.

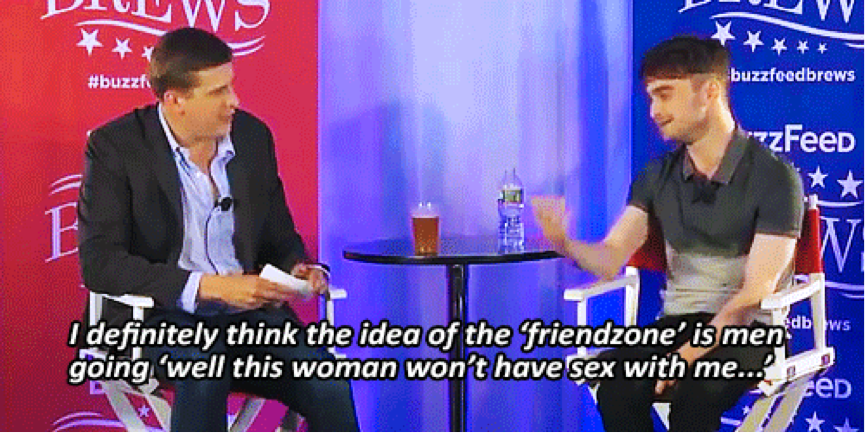

More worryingly, however, the strong need for men to shame women into having relationships with them seems to stem from some kind of patriarchal expectation. There is a strong pressure from Singaporean families to get married and have children, which explains a desire to have a romantic relationship in order to prove their relevance and membership in society. For many people, a relationship is seen as a mark of success, a flag of victory. What many don’t see is that this illusion of the perfect relationship is not essential in one’s emotional and psychological well-being. The Friend Zone can be seen as a harmful and sexist attack on women’s rights, but it can also be the product of incessant pressures to be “with someone” and harsh patriarchal rules.

More worryingly, however, the strong need for men to shame women into having relationships with them seems to stem from some kind of patriarchal expectation. There is a strong pressure from Singaporean families to get married and have children, which explains a desire to have a romantic relationship in order to prove their relevance and membership in society. For many people, a relationship is seen as a mark of success, a flag of victory. What many don’t see is that this illusion of the perfect relationship is not essential in one’s emotional and psychological well-being. The Friend Zone can be seen as a harmful and sexist attack on women’s rights, but it can also be the product of incessant pressures to be “with someone” and harsh patriarchal rules.

Does this sound familiar? These statements are commonly directed towards fat people in attempts to control or police their bodies. Fat-shaming is the act of discriminating against a person because of their weight, and often involves publicly policing fat people’s appearance, behaviour, and attitude. We’ve all likely experienced fat-shaming as a victim, perpetrator or as both.

Does this sound familiar? These statements are commonly directed towards fat people in attempts to control or police their bodies. Fat-shaming is the act of discriminating against a person because of their weight, and often involves publicly policing fat people’s appearance, behaviour, and attitude. We’ve all likely experienced fat-shaming as a victim, perpetrator or as both. How is the policing of women’s body size misogynistic?

How is the policing of women’s body size misogynistic?