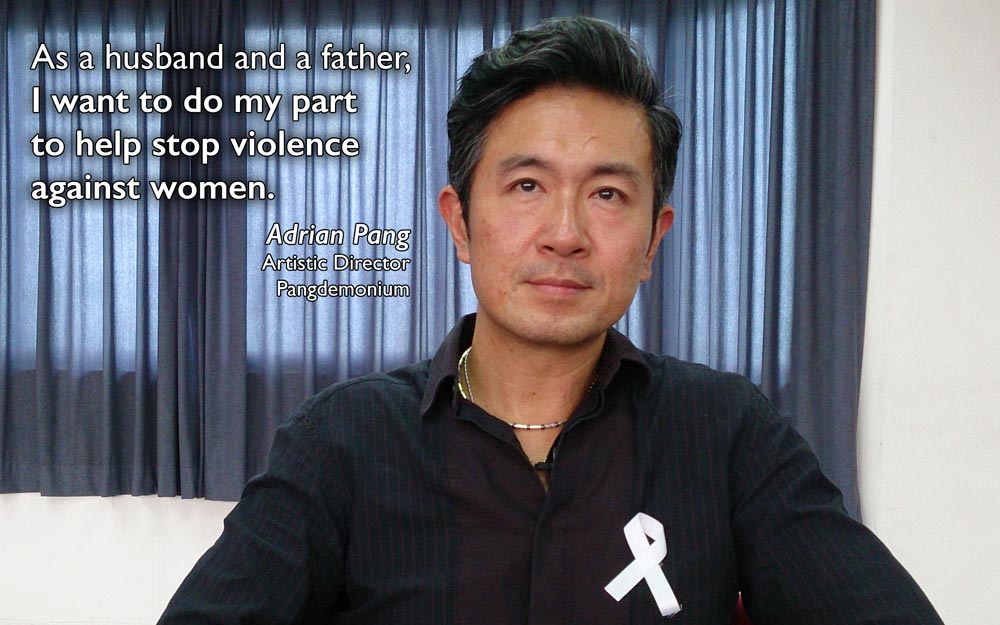

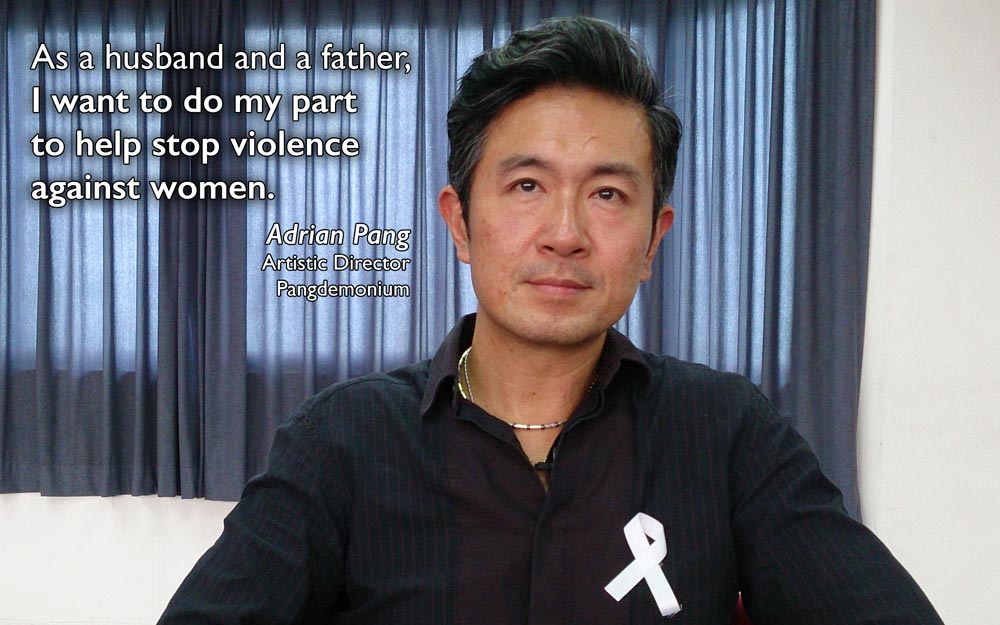

White Ribbon Campaign

This is part 3 of the Understanding Violence guidelines series. Take a look at Part 1 and Part 2!

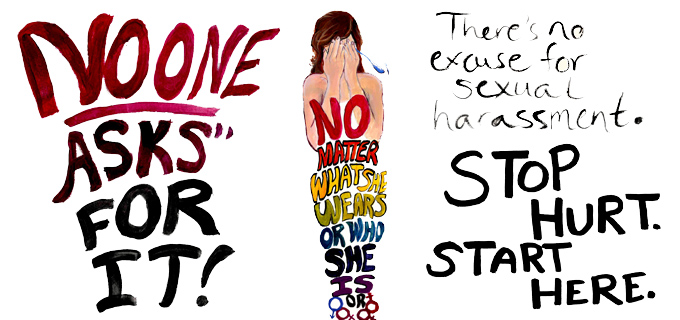

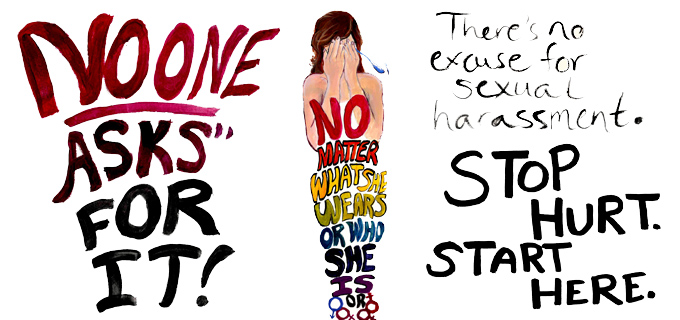

Abusive relationships (e.g. dating abuse, domestic abuse, elderly abuse)

Sexual assault or harassment

This is part 2 of the Understanding Violence guidelines series. Take a look at Part 1 here.

1. Support them through their choices.

1. Support them through their choices.

If they want to make a police report or go to the hospital, offering to go with them for support can make a big difference.

2. Offer resources. Often, people may not realise what options are available to them. Look up resources for support in such a situation, and share them with your friend. It could be a helpline number, free legal services, counselling services, etc. Educate yourself on the available options and discuss them with your friend. If you are able to, and comfortable with it, you can also offer personal resources. For example, they may need some money or a place to stay temporarily while they figure out their next steps.

3. Be sensitive to their position. When a victim of violence is queer, disabled, poor, an ethnic or religious minority, an immigrant, is lacking family support or is facing other societal and structural barriers, they may have even less access to conventional modes of support. Be sensitive to their particular situation, and don’t assume anything about their experience.

4. Encourage them to document their experience(s) of violation or abuse, with as many accurate details as possible. Even if they are not intending to make a police report at present, evidence collection and accounts of their experience can help build a case if they change their mind in the future or if the violence escalates and they want to seek legal recourse.

5. Self care is essential. When our loved ones experience trauma, it often affects us too. While supporting them, we must be responsible in caring for ourselves too and remember to do little things for ourselves that keep our spirits up, and seek help if we need to.

5. Self care is essential. When our loved ones experience trauma, it often affects us too. While supporting them, we must be responsible in caring for ourselves too and remember to do little things for ourselves that keep our spirits up, and seek help if we need to.

6. Encourage them to seek professional help. There are limits to the extent that friends and family can support someone experiencing trauma. Trained professionals can provide support in a multitude of ways, ranging from hotlines and counselling services to legal advice and casework. Encourage them to get the help they need if and when they are ready to.

7. Intervening during an incident of violence can be difficult, and even dangerous, but not impossible. Your safety is top priority. Every situation is different, but some ways people have effectively intervened when they witness sexual harassment or abusive behaviour are:

Think about different scenarios you have been in and strategies that might be helpful. Talk to others about their experiences and strategies.

| Supportive responses | Unsupportive responses |

| • It’s not your fault

• I believe you • We’re here for you • What do you want to do? • What can I do to help? • Should we look up options together? • We can talk about it whenever you want to • This matters. You matter. • You don’t deserve to go through this. • I’m so sorry that happened. • (The perpetrator) is responsible for what happened, not you. • Who else do you trust to talk about this to? • Do you want me or someone else to talk to (the perpetrator)? • Do you want some space? • I’m going to support you no matter what. • You have nothing to be ashamed of. • You didn’t let it happen, (the perpetrator) chose to do it. |

• It’s your own doing

• You can’t call that abuse/rape • You have to leave him! • Don’t take it so seriously • Are you sure? • What were you wearing? • Why did you…? / Why didn’t you…? • You have to take care of yourself better. • Don’t talk to that person anymore. • You chose to date a guy like that • Think about your kids/others • I told you so • Don’t exaggerate/Don’t lie • Just ignore it • Forget about it, it’s no big deal • How could you let this happen? • Let it go/It’s time to get over it • Think about (the perpetrator’s) life • Toughen up/Stop crying • You can’t let people treat you like that • If you weren’t so weak, this wouldn’t happen |

This post was originally published as a Change Maker newsletter in June 2015. If you would like to subscribe to the newsletter for regular updates and tips, take the Change Maker pledge here!

Allyship does not stop at being “pro-gender equality”. To be active allies for gender equality, we need to embrace challenges and lessons along the way.

Allyship does not stop at being “pro-gender equality”. To be active allies for gender equality, we need to embrace challenges and lessons along the way.

As allies, we want to amplify and celebrate the voices of individuals and groups we support. While our experiences of being allies are significant to our own learning (and unlearning) about the issue of gender inequality, we also should not dominate the very conversations that we want to start.

Allyship is not meant to be comfortable.

Being an ally sometimes means being confronted by perspectives that we have been taught to ignore or ideas that have been made invisible. This may mean that we can get confused, defensive or upset, especially when we believe strongly in our own good intentions.

However, allyship is not meant to make us feel comfortable with how we have been thinking. It is a learning journey towards listening to, understanding and respecting other people’s views, stories and lived experiences.

It means that most of the time, we have to listen more than speak out.

What’s one thing you are ready to do to be an ally for gender equality?

1. As our ally, Etiquette SG, puts it, “We believe (change) starts with conversation. And we believe that art starts great conversation.” The arts can be a cool way to bring innovative ideas that have strong social messages to your communities.

2. Learn more about the subject by talking to other advocates, and also victims of sexism, homophobia, or transphobia (but only if they feel comfortable sharing their experiences!).

3. Create a support system by amplifying other groups’ causes as well – just like how Jejaka, a support organisation for queer Muslim men in Singapore, brought the Change Maker workshop to its group last month!

4. UWC Tampines students are working on a Youth Forum to start a dialogue on gender with young people in Singapore. If you’re still in school, work with like-minded peers to support a cause you’re passionate about!

5. Cultivate friendships with other advocates. Having supportive friends can help us become more dedicated allies and make informed choices about the kind of change we want to create.

Get involved

Click here if you are interested in our focus group for male allies! Want to be a volunteer in other ways? Email [email protected]

Updates

You get to choose what kind of guy you are. This year, we are mobilising male Change Makers through various programmes and events. Find out more here!

Consent Revolution are collecting experiences of sex education in Singapore. Got a story fit for “SG Sex Ed Fails”? Submit it here!

Recognise and affirm subtler forms of violence. Less visible forms of violence, like emotional neglect, repeated insults or put downs, control, silencing or dominating one’s partner and verbal/visual sexual harassment often go unnoticed, but can cause victims a lot of distress and trauma, especially when it has been going on for a while. Be careful not to trivialise or minimise their experience.

Recognise and affirm subtler forms of violence. Less visible forms of violence, like emotional neglect, repeated insults or put downs, control, silencing or dominating one’s partner and verbal/visual sexual harassment often go unnoticed, but can cause victims a lot of distress and trauma, especially when it has been going on for a while. Be careful not to trivialise or minimise their experience. People are the best experts of their own lives. Don’t take things into your own hands or try any ways to “help” without the victim’s clear and voluntary consent. For example, you may think it is a good idea to confront the perpetrator, but the victim might feel that doing so will put them (and you) in further danger. Or you may believe that if someone is in an abusive relationship, they should leave their partner. But they may not be ready to do so, and leaving might lead to a new set of difficulties and struggles that they are not prepared to face. Always respect the victim’s choice – they know best. Exercise: Think about and list all the possible reasons why someone may not be able or willing to leave an abusive relationship. Putting ourselves in the shoes of others helps build empathy and allows us to respond in more sensitive ways.

People are the best experts of their own lives. Don’t take things into your own hands or try any ways to “help” without the victim’s clear and voluntary consent. For example, you may think it is a good idea to confront the perpetrator, but the victim might feel that doing so will put them (and you) in further danger. Or you may believe that if someone is in an abusive relationship, they should leave their partner. But they may not be ready to do so, and leaving might lead to a new set of difficulties and struggles that they are not prepared to face. Always respect the victim’s choice – they know best. Exercise: Think about and list all the possible reasons why someone may not be able or willing to leave an abusive relationship. Putting ourselves in the shoes of others helps build empathy and allows us to respond in more sensitive ways.

Anonymous contribution

This is a serious topic. It is also controversial, uncomfortable, and one that I’ve considered voicing before. Even today, I write this with a lot of hesitation.

If I documented all the instances of sexual harassment I’ve encountered, I could probably write chapter or two of a book by now. If someone else told me they had encountered similar situations, I would unequivocally urge them to take action immediately.

Yet it is something I have never done. Why? Because my image and my career are way more important to me. Because I brush it off like I’ve learnt to brush off everything else unpleasant that comes my way (Because that’s life, right?). Because it is not worth the hassle to me. Because apparently not everyone has the same moral compass. Because ours is a society of victim-blaming. Or that is how I have justified it to myself time and again. I know it’s not right. But I also don’t know if this is a cause I want to get up in arms about. Because I’m comfortable in my own coping mechanisms. I am also acutely aware that it is my silence (and the silence of many others) that empowers the perpetrators.

Yet it is something I have never done. Why? Because my image and my career are way more important to me. Because I brush it off like I’ve learnt to brush off everything else unpleasant that comes my way (Because that’s life, right?). Because it is not worth the hassle to me. Because apparently not everyone has the same moral compass. Because ours is a society of victim-blaming. Or that is how I have justified it to myself time and again. I know it’s not right. But I also don’t know if this is a cause I want to get up in arms about. Because I’m comfortable in my own coping mechanisms. I am also acutely aware that it is my silence (and the silence of many others) that empowers the perpetrators.

But today, for me, a nerve was struck. I wonder what gives some men the gall to think they can say or do whatever they want, and it is fine? I imagined myself saying some of the things that have been said to me and I don’t know in what world I would think it okay to say that to another person whom I clearly interact with only in a professional manner, and have never given a reason to think otherwise.

And in each instance and interaction of this kind, it has been crystal clear to me that any respect or regard for my intellect or character is only secondary (if at all existent) to the objectification of my body. It bothers me a lot that in this day and age, capable women, who are in every way equal to their male counterparts, still need to be subjected to this objectification. It bothers me that we as a society have not yet found a solution to these fundamental issues arising out of a lack of respect (and in some cases, even consent).

I don’t know what the answer is, I honestly don’t. And, I am somewhat ashamed to say, I still stand by my very poor coping mechanism of silence. But I do know that as a society we can all do better. A lot, lot better.

Anonymous contribution

What are your views on wearing makeup?

How about your views on Taylor Swift’s music?

Finally, would you ever be a stay-at-home parent?

What if I told you that you had to pass the above test to confidently call yourself a feminist?

Luckily, and perhaps frustratingly for people looking for easy answers, every response in this test is valid. One of the dilemmas that new feminists run into early on is that of trying to reconcile their lifestyle choices with their philosophy. These range from the mundane (is it alright if I enjoy James Bond movies?) to the more definitive (can I take my husband’s last name after we get married?). What remains the same, though, is the idea that a basket of lifestyle choices can make or break one’s identity as a feminist.

Luckily, and perhaps frustratingly for people looking for easy answers, every response in this test is valid. One of the dilemmas that new feminists run into early on is that of trying to reconcile their lifestyle choices with their philosophy. These range from the mundane (is it alright if I enjoy James Bond movies?) to the more definitive (can I take my husband’s last name after we get married?). What remains the same, though, is the idea that a basket of lifestyle choices can make or break one’s identity as a feminist.

The assumption undergirding this way of thinking is that feminism is a homogenous movement. It is not. Going by the basic understanding that feminism’s goal is to achieve gender equality for all, we need to appreciate that there are many means to that end. Feminists straddle many different identities – they differ in sexuality, class, race and many other lines. It makes sense then that such a diverse group of people would have dissimilar and, occasionally contradictory, approaches to fighting for gender equality.

There are two implications of this realisation; the first is that the burden of being the “model feminist” is lifted off the individual. All too often, new feminists feel the pressure of setting an example of what it means to believe in gender equality through their actions and end up feeling conflicted because there is no straightforward answer to be found. The second is that, amidst our inevitable disagreements, there is little point in quarrelling about what is or is not “feminist enough”. News now travels at the speed of light and every action or word from a famous woman is sufficient fodder for a thousand think pieces. There is merit in having conversations like this however they shouldn’t be definitive.

There are two implications of this realisation; the first is that the burden of being the “model feminist” is lifted off the individual. All too often, new feminists feel the pressure of setting an example of what it means to believe in gender equality through their actions and end up feeling conflicted because there is no straightforward answer to be found. The second is that, amidst our inevitable disagreements, there is little point in quarrelling about what is or is not “feminist enough”. News now travels at the speed of light and every action or word from a famous woman is sufficient fodder for a thousand think pieces. There is merit in having conversations like this however they shouldn’t be definitive.

Once we accept the plurality of the feminist experience, we open ourselves up to the opportunity to learn about feminists from all walks of life are resisting oppression and creating a better world to live in.

This post was originally published as a Change Maker newsletter in October 2015. If you would like to subscribe to the newsletter for regular updates and tips, take the Change Maker pledge here!

I’m a guy, and I care about sexism. What can I do?

1. INTERRUPT: Sexism and “guy talk”

Catch-ups with your National Service buddies, soccer hang-outs, or just drinks with guys you like to hang out with – these traditionally “boys-only” spaces provide a lot of potential for allies to interrupt sexism should it arise.

Catch-ups with your National Service buddies, soccer hang-outs, or just drinks with guys you like to hang out with – these traditionally “boys-only” spaces provide a lot of potential for allies to interrupt sexism should it arise. People aren’t always going to pat us on the back for speaking up. In order to spark real change, men need to be okay with starting conversations that nobody wants to have, and dealing with discomfort. You need to listen keenly to women’s experiences and take them seriously. Read about and follow broader discussions on gender issues that are happening now. Learning requires humility and willingness to unlearn male privilege. Speaking up is taking a risk. Are you ready for it?

People aren’t always going to pat us on the back for speaking up. In order to spark real change, men need to be okay with starting conversations that nobody wants to have, and dealing with discomfort. You need to listen keenly to women’s experiences and take them seriously. Read about and follow broader discussions on gender issues that are happening now. Learning requires humility and willingness to unlearn male privilege. Speaking up is taking a risk. Are you ready for it? Think about the communities you are already a part of and how you can make a difference there. In specific, think of the spaces where you have leadership and a strong voice. This might be at home, on an online space, in an interest group or a work team. For example, if an organising team you are in wants to invite a group of experts for a panel discussion, what are the factors you would consider? Is there equal representation of men and women on the panel? Are there people dominating the conversations and decision-making processes? How much of a role do women play in organising and participating? How major are these roles and how much are women acknowledged or credited for them?

Think about the communities you are already a part of and how you can make a difference there. In specific, think of the spaces where you have leadership and a strong voice. This might be at home, on an online space, in an interest group or a work team. For example, if an organising team you are in wants to invite a group of experts for a panel discussion, what are the factors you would consider? Is there equal representation of men and women on the panel? Are there people dominating the conversations and decision-making processes? How much of a role do women play in organising and participating? How major are these roles and how much are women acknowledged or credited for them?

by Kimberly Jow, Change Maker

Hey you,

Here is a tweet I saw you retweeting, which inspired my letter to you.

Internalised misogyny is upsettingly common. The words flash in my head like the visual representation of a siren whenever I hear the words, “I am not like other girls.” So no, you are not alone, and here is why that is a problem.

The composing of this tweet was deliberate. Social media lulls you into a false sense of anonymity, as if you can truly escape responsibility for the things you say on Twitter. In truth, tweeting something offensive is pretty much akin to inviting all your followers into a conference room and shouting your tweets at them through a megaphone. For the person running the above account, that comprises many, many people, most of whom she probably doesn’t know in real life. For us non-famous Twitter users, though, the conference room may be smaller, but remains valid. Composing a tweet like this lets all your Twitter followers know that you find girls annoying, and that you hate the fact that you are one. It tells them many things: that you are ashamed of your own gender, that girls are to be hated, and most importantly, that it is perfectly fine to shame girls – all girls – for one apparently unforgivable quality that you think should be called out. Tweeting the less than 140 characters invites your barest online acquaintances to collectively witness your spitting on your entire gender.

Retweeting this is close to writing the tweet. I barely know you, but I can tell from your tweets that you think this is funny, and it’s just a joke. To a tiny extent, it is. But that doesn’t make it harmless. The fact that you retweeted it allows your followers to see that you, an acquaintance of theirs, agree with its contents. This is no longer an “American thing”, nor is it that far off from their reality, because there you are, their classmate, their friend from church, or their neighbour, agreeing that girls are annoying and it’s terrible to be one. Suddenly, the tweet is no longer just hers. It is also yours. You have endorsed it and what it stands for.

Retweeting this is close to writing the tweet. I barely know you, but I can tell from your tweets that you think this is funny, and it’s just a joke. To a tiny extent, it is. But that doesn’t make it harmless. The fact that you retweeted it allows your followers to see that you, an acquaintance of theirs, agree with its contents. This is no longer an “American thing”, nor is it that far off from their reality, because there you are, their classmate, their friend from church, or their neighbour, agreeing that girls are annoying and it’s terrible to be one. Suddenly, the tweet is no longer just hers. It is also yours. You have endorsed it and what it stands for.

A woman’s validation of misogynistic comments is oftentimes used by sexist people to fuel their sexism, allowing them to generalise your acceptance of sexism to everyone.

Common usages of such validation includes the infamous words, “I have a female friend who agrees that…”. (At this point, I’m not too sure if people do say this elsewhere, or the exceptions who say this are just constantly around me, but the prevalence of this phrase in my social circle shrouds me like a suffocating cloud of unprocessed raw wool from some kind of sexist sheep.) Sexists who see your retweets can and have used it as validation of their own problematic attitudes. For example, a man could tell a woman that girls are all annoying, and bring your retweet up as evidence in the face of rebuttals.

I know you didn’t mean to do all that. But intent is not impact. The fact that you have attempted to alienate yourself from the rest of your gender suggests that you think your gender is not worth standing up for, and have invited others to attack them. This stands true whether or not you really meant to do so.

The above may sound accusatory and didactic, or unnecessarily harsh, but you have indeed accidentally done all of this. While my words are not coming from a place of anger nor blame, I do want to reach out to you and tell you the effects of your actions. I think it is time you put aside your desire to tell girls in short skirts that they are sluts, or your love for books as something other girls don’t have that makes them stupid. I also think it is time you stop seeing men’s approval as the ultimate goal for everyone, nor seeing misogyny as a tool to be more relatable to men. The road to eradicate sexism seems daunting, but small steps like changing your attitude towards fellow women is actually a great leap.

I am sorry that I never dared to actually tell you any of this, but I know it isn’t too late. I am happy that we can keep working to fight for your right to stand amongst men as equals, and I can only hope that one day you will join us.

About the Author: Kimberly is a somewhat ambitious NUS undergraduate who has always dreamed of writing her own About the Author section. She retains much hope for eventual equality, and is willing to fight the currents to get there.

Anonymous post, as part of our “What does being a man mean to you?” blog series. Submit your responses to [email protected]!

Being a man means so many other things than just body shape, and these perceptions have been shaped by my family, my friends and society at large. Being a man means being tough, loyal, intelligent, fit and sporty. If you are a man, you are also expected to be a natural leader and a gentleman. My father would always remind me that boys should play sports and keep fit at all times, and that the performing arts is more for girls. He wanted me to be more involved in sport and stay away from “girly” activities.

Being a man means so many other things than just body shape, and these perceptions have been shaped by my family, my friends and society at large. Being a man means being tough, loyal, intelligent, fit and sporty. If you are a man, you are also expected to be a natural leader and a gentleman. My father would always remind me that boys should play sports and keep fit at all times, and that the performing arts is more for girls. He wanted me to be more involved in sport and stay away from “girly” activities.

I never understood why he acted as if the interests that one pursues has anything to do with one’s gender identity. While I do play sports and exercise regularly, it is only because it is necessary for health and fitness. This has nothing to do with what society expects boys and men to do or trying to achieve that coveted muscular body. It is unfortunate that sport is seen as an activity that all boys and men are expected to engage in in order to be seen as manly, tough and strong.

Society tends to think of a man as having to protect women and show leadership over them. He must never appear weak, or else he will be ostracised and looked down upon by society. He must never cry because only girls cry. He must always appear confident, walk in a confident posture, talk in a confident manner. He must have a lean and strong body that exuberates an aura of confidence and dominance. He must always be dominant to females or else he would look like a joke.

Society tends to think of a man as having to protect women and show leadership over them. He must never appear weak, or else he will be ostracised and looked down upon by society. He must never cry because only girls cry. He must always appear confident, walk in a confident posture, talk in a confident manner. He must have a lean and strong body that exuberates an aura of confidence and dominance. He must always be dominant to females or else he would look like a joke.

With all these restrictions and expectations placed on him, he must be very careful to not just be a man, but also appear and act like a man, or else he would be labelled weak, gay, sissy and a variety of other names. Not only is this image highly damaging to women in society (conversely, women are seen as the weaker sex who should be subservient and obedient to the whims of men), it is clear that such a misguided attitude of what a man should be hurts every single boy and man who isn’t like that, and that’s most of us right there.

I say that boys and men should stop doing all the things that we do only because we feel it is expected of men. I have a good relationship with my schoolmates, but I sometimes feel pressured to “be a man” in their presence. For example, when we go to Universal Studios together, I will be pressured to go on intense roller coasters even though I do not want to and I do not like the feeling of riding them. Of course I would always refuse and my friends would try to persuade me. Men should be daring, courageous and adventurous, so does my refusal make me less of a man? In the end, this is just a small matter and they do accept my views eventually, but this is just one of the many examples of how men face pressure in different ways to prove their worth in manliness.