by Foo Jun Kit, Change Maker

I wasn’t sure what to expect when I signed up for the Change Maker Workshop. Prior to this, I thought violence only referred to physical and sexual abuse. I expected a lecture on the severity of rape and tips on how to deal with rape cases, but walked out of the room gaining much more than that.

My initial notions on violence against women were already proven wrong right from the start. Violence is much more than physical and sexual abuse; it includes many other aspects such emotional abuse, intimidation and economic abuse. During the workshop, we were exposed to several scenarios, demonstrating how gender-based violence can occur all around us without us being aware. Gender-based violence could happen in a workplace, a party, or even at home! It happens everywhere, and we should be able to identify them and intervene if possible.

What struck me most was learning about victim blaming. I never knew that such an issue was so relevant to me. Victim blaming, as the name suggests, refers to wrongly shifting the blame onto a victim. This makes them feel worse about what they went through when we should be offering support and assistance to them instead. After all, they have experienced something traumatic. This idea of victim blaming may sound foreign to some, but common phrases such as “why didn’t you…” or “you could have…” are examples of victim blaming.

In fact, instead of additionally pressurising an already distressed victim, it is only right to help them by offering them options and respecting her decision. For example, support the rape victim’s decision not to seek professional advice. It is very easy for a bystander to tell her to make a police report, but we are often unable to fully comprehend the situation and the feelings of the victim. If we impose our opinions on the victim instead of helping her, it may cause her further emotional stress because our decisions may not be entirely suitable for her situation. Therefore, think twice before blaming a victim for an incident or instructing her on what action to take. Rather, talk to her and support her decisions. This is crucial because the first person the victim consults impacts her decisions the most.

Some recent events also perpetuate violence against women, especially victim blaming. Just last year, the Singapore Police Force put up a poster addressing molestation with the tagline “Don’t get rubbed the wrong way.” This advertisement is a perfect example of victim blaming. By instructing women to “have someone escort you home when it is late”, “avoid walking through dimly lit and secluded areas alone” and “shout for help and call 999, don’t be a silent victim”, molesters are absolved of blame. The message seems to imply that it is the victim’s fault for getting molested because she did not protect herself well. This should not be the case. While these crime prevention posters have good intentions, they should really be targeting the molesters instead of telling victims to prevent sexual assault. That way, victims can be assured that being molested was not their fault.

Some recent events also perpetuate violence against women, especially victim blaming. Just last year, the Singapore Police Force put up a poster addressing molestation with the tagline “Don’t get rubbed the wrong way.” This advertisement is a perfect example of victim blaming. By instructing women to “have someone escort you home when it is late”, “avoid walking through dimly lit and secluded areas alone” and “shout for help and call 999, don’t be a silent victim”, molesters are absolved of blame. The message seems to imply that it is the victim’s fault for getting molested because she did not protect herself well. This should not be the case. While these crime prevention posters have good intentions, they should really be targeting the molesters instead of telling victims to prevent sexual assault. That way, victims can be assured that being molested was not their fault.

Come spend a bit of your time to find out more about victim blaming and other pertinent gender-based violence issues such as rape culture and privilege. Schedules for the monthly Change Maker workshops can be found at the We Can! Singapore website. I assure you, your time will be very well spent!

About the Author: Jun Kit is a Year 4 student at Raffles Institution, although often mistaken to be primary school student due to his massive height. He is an avid fan of football but enjoys playing badminton too. Maybe one day, he’ll represent Singapore at the World Cup and lead the country to glory. Besides playing sports, he is also a fan of writing and has his own blog page, albeit filled with football content. But at the moment, he’s focused on his studies and is all pumped up for the upcoming O Level Higher Chinese Examinations. Right.

About the Author: Jun Kit is a Year 4 student at Raffles Institution, although often mistaken to be primary school student due to his massive height. He is an avid fan of football but enjoys playing badminton too. Maybe one day, he’ll represent Singapore at the World Cup and lead the country to glory. Besides playing sports, he is also a fan of writing and has his own blog page, albeit filled with football content. But at the moment, he’s focused on his studies and is all pumped up for the upcoming O Level Higher Chinese Examinations. Right.

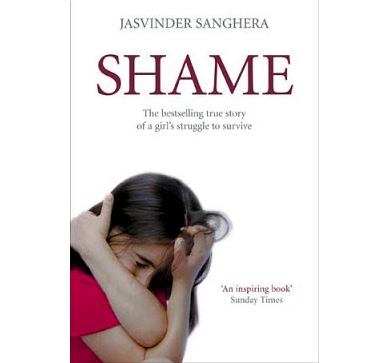

I just finished the book ’Shame’, which is about forced marriage, honour killings and domestic violence in the South Asian diaspora of Britain. The author is a Sikh woman from Derby who survived very brutal oppression and violence by her family and community, and has spent her life supporting and advocating for other South Asian women and girls in Britain, mostly of Pakistani origin, who’re affected by the same conditions she was in.

I just finished the book ’Shame’, which is about forced marriage, honour killings and domestic violence in the South Asian diaspora of Britain. The author is a Sikh woman from Derby who survived very brutal oppression and violence by her family and community, and has spent her life supporting and advocating for other South Asian women and girls in Britain, mostly of Pakistani origin, who’re affected by the same conditions she was in.