Written by Estelle Ng, Change Maker

In December 2015, an article published in The Straits Times caught my attention. Entitled “Transgender man with 2 ‘wives’ admits sex with teenage girl”, it was an extremely uncomfortable and confusing read.

In December 2015, an article published in The Straits Times caught my attention. Entitled “Transgender man with 2 ‘wives’ admits sex with teenage girl”, it was an extremely uncomfortable and confusing read.

Here’s why:

- In short, it was a case about a man who is charged with having sex with a minor.

- The word “married” is placed in inverted commas – making it unclear as to whether he really is married. If they are legally married, there should be no reason why “married” should be accompanied by inverted commas. Furthermore, it is unclear if his marital status(es) matter.

- He was constantly referred to as “her” even though his gender identity clearly shows otherwise.

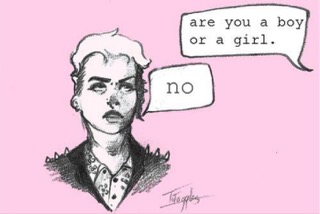

- It is unclear if his gender identity actually matters in this case. Think about it, would his gender identity and/or orientation be worth a mention if he was cisgender? “Cisgender man with 2 ‘wives’ admits sex with teenage girls”. If not, is there really a need to identify him as a “transgender” while at the same time denying his gender identity?

The choice of words and language used in the recent newspaper report reflects a less-than-dignified representation of individuals from the trans community. And my opinion is even echoed in an unpublished letter written by Sayoni to the Straits Times.

Talking about how the trans community is represented in media is important because it reflects how they are treated in society. More importantly, it also deals with any social biases and prejudices they face in society.

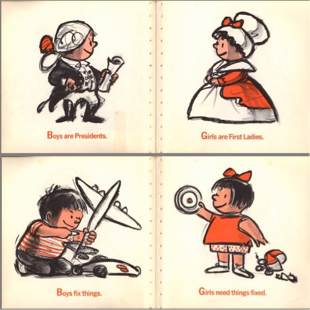

Surely, in this day and age, there has to be more respectful representations of trans individuals in Singapore. Afterall, trans individuals are just like you and me – we go to school, get a job and pay due taxes. The only difference is in the bodies we identify ourselves in: yet, don’t we all have a unique way of identifying our preferred gender and performance as well?

Having said that, how can we best represent individuals from this community? Let’s take a look at three note-worthy media representations!

- The New Paper’s “Mum, Am I a boy or a girl? Singaporean transgender individuals open up about struggles”

Shortly after the above mentioned case was made public, TNP made the effort to engage in conversations with a few trans folks. In the report, trans individuals were given a chance to narrate their life stories. It featured three individuals: Cheong who shared about how she had to live under her mother’s expectations of her as a boy when she was growing up; Khor who spoke about his transition; and Salamat who expressed her joy after becoming who she really felt like. Though featuring three individuals cannot wholly represent experiences that all trans individuals face, the article humanises trans individuals and treats them with respect by giving them room to share their stories the way they want to.

- Grace Baey’s photo exhibition, 8 Women

If a picture speaks a thousand words, Baey would have spoken a great amount by bringing them in the limelight in the way the featured 8 individuals were comfortable with. Entitled 8 Women, this photo exhibition highlights how trans folks exist in diversity – each one is unique in their own right.

-

Christopher Khor’s upcoming film-documentary, Some Reassembly Required

Christopher Khor’s upcoming film-documentary, Some Reassembly Required

In an upcoming documentary, Khor features trans folks in different stages of transition. But, really this documentary is about what it means to be human for some individuals in a “modern country with conservative Asian values”.

In sum, various media platforms have an important role to play in providing information and educating the public. It is essential that information is tactfully chosen and media works are thoughtfully crafted and presented. Being insensitive to a person regardless of gender identity or orientation is not only disrespectful but also serves to fuel discrimination that the LGBTQIA community is already facing in Singapore.

It is time to recognise that trans folks are individual human beings who deserve respect too. After all, identifying with a particular life experience or gender identity is only a part of one’s identity.

“I am who I am (which is the sum of my experiences) but being transgender specifically is not the centre of my being… I think it’s become so much a part of me that I would not be who I am without it, but does it define me? I don’t think so.,” he offers. “We really are just the sum of our life experiences, and being transgender is just one part of mine.”

– Christopher Khor in an interview with Contented.

About the Author: Living by the motto permanent impermanence, Estelle realises that with every moment never capable of repeating itself, life is simply too short to be spent waiting for things to happen. She is currently a Sociology undergraduate who believes that the power of words and the arts can inspire conversations.

About the Author: Living by the motto permanent impermanence, Estelle realises that with every moment never capable of repeating itself, life is simply too short to be spent waiting for things to happen. She is currently a Sociology undergraduate who believes that the power of words and the arts can inspire conversations.

Transphobia is also reinforced by the underrepresentation of trans people. Rarely do we see trans people being adequately represented in governance, civil society or the media. This creates ignorance: people tend to form stereotypes of trans people from whatever little they are exposed to – my first exposure to the word “transgender” came in the form of a disparaging insult toward how another person looked. Trans identities are relegated to punchlines about vacations in Bangkok and deemed perverted or unnatural. It becomes easy to demonize entire groups of people you don’t know much about, but the fact remains that trans people do exist and they don’t just come in the form of shimmying drag queens (they can, and there’s nothing wrong with that!) – they lead human lives as do all of us.

Transphobia is also reinforced by the underrepresentation of trans people. Rarely do we see trans people being adequately represented in governance, civil society or the media. This creates ignorance: people tend to form stereotypes of trans people from whatever little they are exposed to – my first exposure to the word “transgender” came in the form of a disparaging insult toward how another person looked. Trans identities are relegated to punchlines about vacations in Bangkok and deemed perverted or unnatural. It becomes easy to demonize entire groups of people you don’t know much about, but the fact remains that trans people do exist and they don’t just come in the form of shimmying drag queens (they can, and there’s nothing wrong with that!) – they lead human lives as do all of us.