by Lee Wan Yii, Change Maker

If you’ve been following recent celebrity news, you would have noticed the huge uproar over a portion of Patricia Arquette’s backstage speech after the Oscars (watch 2:16 to 2:36). In feminist circles, the word “intersectionality” is thrown around a lot, and this recent controversy has the brought the word into light a lot more. Everyone’s asking for intersectional feminism to be brought to the table and for us to fight for “all women”.

But just what is intersectionality? I think this is a great teachable moment for everyone about the topic, and what we should do about it.

What It Is

Let’s first break down Arquette’s exact words to understand exactly why they were so controversial:

Let’s first break down Arquette’s exact words to understand exactly why they were so controversial:

“So the truth is, even though we sort of feel like we have equal rights in America, right under the surface, there are huge issues that are applied that really do affect women. And it’s time for all the women in America and all the men that love women, and all the gay people, and all the people of color that we’ve all fought for to fight for us now.”

Arquette seems to have her heart in the right place – she’s calling out the pervasive problem of gender inequality, and is calling for people to help empower women and level the playing field (earlier on, she was addressing the specific issue of wage inequality between men and women). She’s saying loud and clear that there is a problem that needs to be fixed, because it’s not okay for men to have a systemically sexist advantage over women. Shouldn’t feminists applaud that rallying call rather than tear her down for it?

I think there are a some problems with her statement, which reveal that as she fights sexism in her own way, she still has clear misconceptions about racism and LGBTQA+ issues. Her statement suggests:

- That the groups “women”, “men that love women”, “gay people”, and “people of colour” are all separate categories of people, instead of possibly overlapping aspects of identities. (For one, there are many queer women of colour out there!)

- That the fight for “all the gay people” and “all the people of colour” is separate from and less important than the fight for women.

- That the former two are over or close to over, while the fight for women is not.

- That women have been involved in fighting for “all the gay people” and “all the people of colour”, and so the latter two groups somehow owe/are in debt to women for their progress.

Her seemingly harmless statement ignores some basic realities about people, identity, and the fight for social justice. When she says “we”, she doesn’t seem to be referring to all women – she seems to be referring to a specific group of women: namely white, heterosexual women. And so this begs the question: what about everyone else?

Here’s where intersectionality comes in!

The term refers to the connections between forms of oppression or discrimination. In every system of oppression, there is a group that is disadvantaged based on their identity (e.g. women being discriminated against because of their gender), while there is another group that is privileged based on their identity. And because people have many aspects to their identities (e.g. gender, race, sexual orientation, class, and other identity markers), each individual’s experience in society turns out to be unique.

For example, someone may identify as a female – but beyond that, she would also identify with a race, belong to a certain socioeconomic class, and fall into many other social categories and systems. She may be privileged due to how she identifies in some ways, and oppressed due to others.

Therefore, intersectionality recognises the following:

- Everyone has many different parts to their identities.

- Everyone is somehow privileged/disadvantaged by various systems of discrimination, e.g. racism, sexism, LGBTQA+ discrimination, ableism, etc., in different ways.

- We don’t want to make various social justice causes mutually exclusive, or reinforce some forms of oppressions while combatting others.

- We don’t want to force people to choose between different parts of their identity. (Would a woman of colour have to say, “Let’s pause the fight against racism to help women get equal pay!” in response to Arquette?)

And so an intersectional feminist would say, “All women of all backgrounds are victims of gender inequality, and so we’re going to fight for and with all of them, without disregarding, or worse, reinforcing, any other forms of oppression!”

What to Do

What to Do

Intersectionality applies to everyone, and all social justice causes should be taken up in light of it.

If we wish to strive for gender equality, then we have to acknowledge that the journey is intertwined with other goals of breaking down racism, homophobia, ableism, transphobia and more. Being a feminist means fighting for gender equality for all people. When we aim to eliminate gender-based violence, we are aiming to do so for everyone, including (if not especially) for those who suffer as a result of other forms of oppression as well.

One important step everyone can take is to understand and check privilege.

I identify as female. At the same time, I enjoy Chinese and cisgender privilege in Singapore. And so, I understand that while I can empathise with the oppression women experience due to sexism in society, my experience is limited when it comes to other forms of marginalisation. While knowing this, I hope to engage everyone in feminist dialogue and listen to them when they speak rather than speaking over them when it is beyond my experience to do so. Even with a nonabrasive personality, I try to call out insensitive remarks among my peers as much as possible. And I also hope for my peers to check me whenever I do or say anything that reinforces stigma or oppression, which helps steer my path towards understanding and changing my place in society.

This leads me to my second point on empathy.

It is difficult to fully understand certain kinds of marginalisation if we are not ourselves the victims of them. Our deepest empathy has limits. But is it the attempt to put ourselves in the shoes of others and remind ourselves of the struggles of fellow human beings which allows for a broad, intersectionalist fight for all. Contrary to some misconception, understanding intersectionality helps us be more inclusive, kind, understanding, and powerful as we tread the path towards equality.

And this empathetic effort extends to everyone, including people like Arquette. Sometimes we do need to ask whether it is productive to immediately hurl vitriol at them, or point out the effects of their words and actions in an honest, effective dialogue. The latter is possible if her heart truly comes from a well-meaning place.

As I personally find out how to best combat gender inequality and gender-based violence, I am searching for the path that is most progressive, effective, and inclusive. Showing an understanding of intersectionality and acting on it is one big step along that path.

About the Author: Lee Wan Yii is a student waiting to enter university, and is now spending her free time knitting, brushing up on her French, getting her license, learning Kapap, and writing, among other things. She enjoys good music as much as she enjoys good conversation.

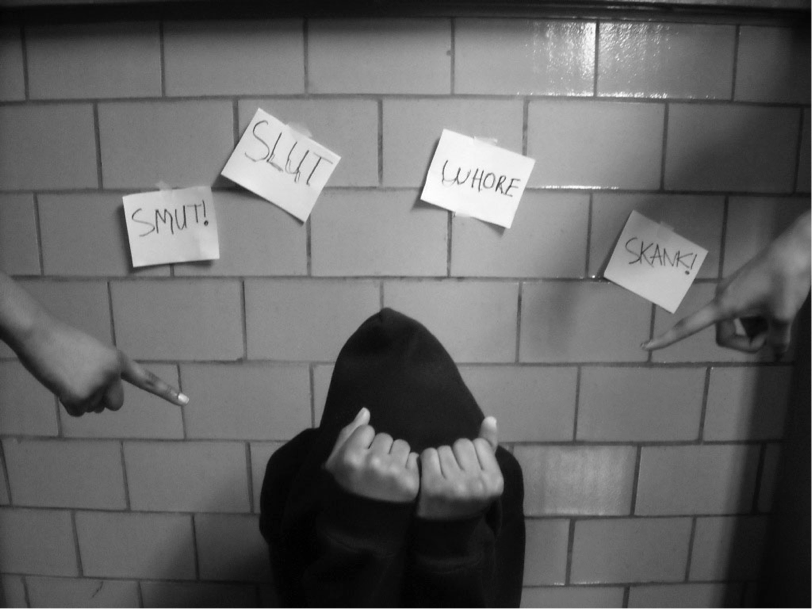

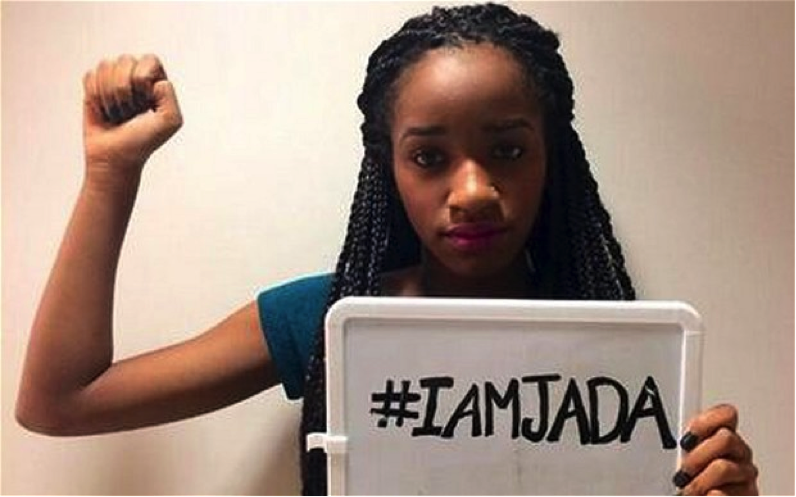

Increasingly, the proliferation of social media and the ability to hide behind anonymity have fuelled malicious attacks on individuals perceived as sexually promiscuous. In 2013, the hashtag #slanegirl was particularly infamous, as Twitter users collectively denounced a girl caught performing oral sex at a concert venue, with some even going to the extent of publishing her full name and age on online public spaces. More recently, schools in USA are facing protests after humiliating students who were perceived to be inappropriately dressed by forcing them to wear loose fitting “shame suits”. Such behavior, however, irresponsibly perpetuates the damaging outlook that victims are responsible for their own plight, while removing responsibility from perpetrators.

Increasingly, the proliferation of social media and the ability to hide behind anonymity have fuelled malicious attacks on individuals perceived as sexually promiscuous. In 2013, the hashtag #slanegirl was particularly infamous, as Twitter users collectively denounced a girl caught performing oral sex at a concert venue, with some even going to the extent of publishing her full name and age on online public spaces. More recently, schools in USA are facing protests after humiliating students who were perceived to be inappropriately dressed by forcing them to wear loose fitting “shame suits”. Such behavior, however, irresponsibly perpetuates the damaging outlook that victims are responsible for their own plight, while removing responsibility from perpetrators.

Transphobia is also reinforced by the underrepresentation of trans people. Rarely do we see trans people being adequately represented in governance, civil society or the media. This creates ignorance: people tend to form stereotypes of trans people from whatever little they are exposed to – my first exposure to the word “transgender” came in the form of a disparaging insult toward how another person looked. Trans identities are relegated to punchlines about vacations in Bangkok and deemed perverted or unnatural. It becomes easy to demonize entire groups of people you don’t know much about, but the fact remains that trans people do exist and they don’t just come in the form of shimmying drag queens (they can, and there’s nothing wrong with that!) – they lead human lives as do all of us.

Transphobia is also reinforced by the underrepresentation of trans people. Rarely do we see trans people being adequately represented in governance, civil society or the media. This creates ignorance: people tend to form stereotypes of trans people from whatever little they are exposed to – my first exposure to the word “transgender” came in the form of a disparaging insult toward how another person looked. Trans identities are relegated to punchlines about vacations in Bangkok and deemed perverted or unnatural. It becomes easy to demonize entire groups of people you don’t know much about, but the fact remains that trans people do exist and they don’t just come in the form of shimmying drag queens (they can, and there’s nothing wrong with that!) – they lead human lives as do all of us.