by Kelvin Ng Jiawin, Change Maker and participant at Body/Language creative writing workshop

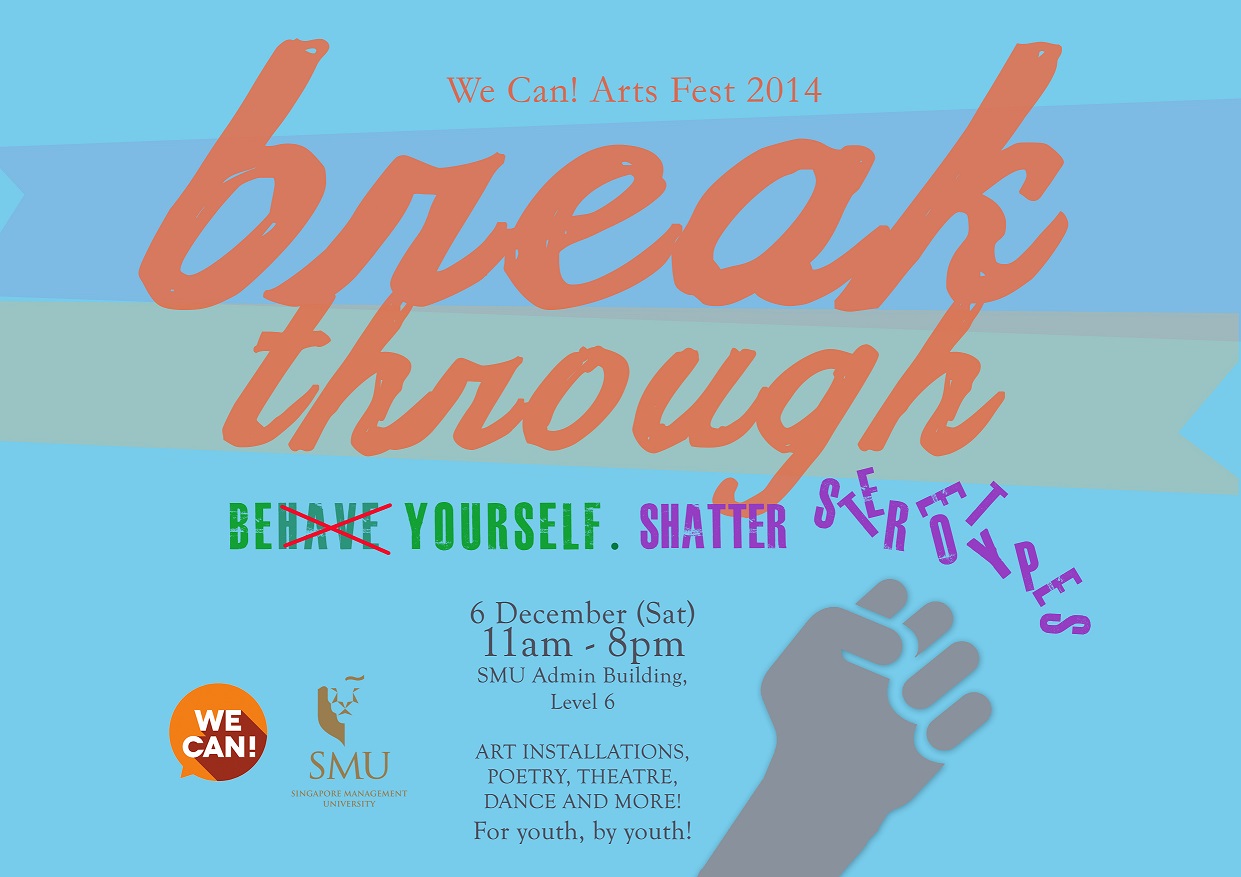

I joined Body/Language, a creative writing workshop developed by EtiquetteSG and We Can! Singapore, for a simple reason: it combined writing and feminism, two of my favourite things. Needless to say, my expectations for the workshop were high. What I did not expect, however, was how much I gained from the workshop in return — besides affording me a creative platform to express my personal experiences with gender issues, the workshop prompted me to reevaluate my own conception of gender-based violence.

I joined Body/Language, a creative writing workshop developed by EtiquetteSG and We Can! Singapore, for a simple reason: it combined writing and feminism, two of my favourite things. Needless to say, my expectations for the workshop were high. What I did not expect, however, was how much I gained from the workshop in return — besides affording me a creative platform to express my personal experiences with gender issues, the workshop prompted me to reevaluate my own conception of gender-based violence.

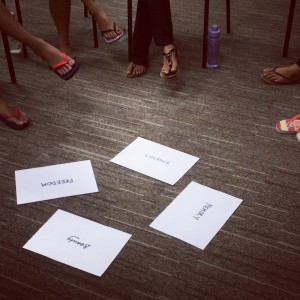

A wide range of topics were covered throughout the four sessions, as my fellow participants and I discussed issues of beauty standards, religion, gender stereotypes as well as institutional sexism. Manessa Lian, a public workshop participant, says, “It was an empowering experience, to be able to use poetry to talk about things that otherwise are rarely voiced out.”

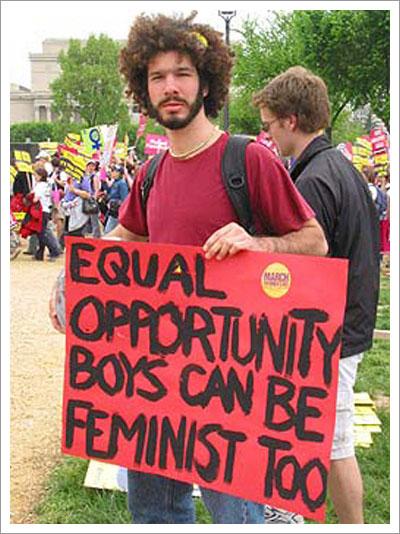

Despite being the only (cisgender) male in the workshop, I never once felt left out, not only because I was able to share my own experiences with deviating from gendered ideals, something I’ve never been able to do comfortably in a mainstream setting, but also because I truly learned a great deal about how issues usually thought of as trivial, such as daily microaggressions, can realistically perpetuate more harm than we’d like to think.

The facilitators of my workshop, Nurul and Anne, were nothing short of stellar. They were simultaneously professional and personal throughout the four sessions, and succeeded in fostering an atmosphere comfortable enough for everyone to share their honest opinions. I particularly liked the ground rules democratically established on the first day, initiated by Anne; it provided a useful framework for our later discourse and ensured that no boundaries were transgressed.

The facilitators of my workshop, Nurul and Anne, were nothing short of stellar. They were simultaneously professional and personal throughout the four sessions, and succeeded in fostering an atmosphere comfortable enough for everyone to share their honest opinions. I particularly liked the ground rules democratically established on the first day, initiated by Anne; it provided a useful framework for our later discourse and ensured that no boundaries were transgressed.

I wasn’t the only one who felt this way; Sahar Pirzada, a fellow GEC workshop participant, says, ”The environment created by the facilitators of the course was one of warmth, support and trust. I felt safe to put my unique voice out there without fear of judgement from the facilitators or my peers. The positive support I received from the participants in my cohort of Body/Language encouraged me to perform at SWF.”

Knowing that it would be the first time performing a spoken word piece for most of us, Nurul also helpfully shared a few spoken word videos so we’d have a better idea of the techniques and forms that could undergird our works. At the same time, however, it was emphasised that we didn’t have to confine ourselves to any format or structure, and encouraged us to express ourselves in the most comfortable way, however informal or unstructured. Anung D’Lizta, a HOME workshop participant, opined that, “A lot of our feelings can’t be talked about, but it can be shared through our writing.”

As we began producing our works in one of the later sessions, the facilitators would go beyond providing helpful technical advice — they’d also initiate a conversation with us to understand where we were coming from, and why we wrote what we did. It was all done in a respectful, understanding manner, and other than providing a catharsis of sorts, both facilitators also shared really germane advice on our personal issues. Throughout the workshop, there was a significant amount of time devoted to conversing with each participant personally, yet in the end, no one was left out and everyone was catered to.

As we began producing our works in one of the later sessions, the facilitators would go beyond providing helpful technical advice — they’d also initiate a conversation with us to understand where we were coming from, and why we wrote what we did. It was all done in a respectful, understanding manner, and other than providing a catharsis of sorts, both facilitators also shared really germane advice on our personal issues. Throughout the workshop, there was a significant amount of time devoted to conversing with each participant personally, yet in the end, no one was left out and everyone was catered to.

My facilitator, Nurul, shares, “It’s a beautifully designed workshop program that enables participants to tap into their inner writing warriors, most of which is driven by personal experiences that they have never or yet to articulate. It was evident that for most of the participants, it became a cathartic outlet to express themselves, not just through words, but through poetry, which allowed for a more creative and powerful resolution. The workshops also presented many participants the opportunity to discuss issues on a wider scale, having come with different perspectives on different issues.”

I had mixed feelings about sharing and performing my piece in front of the class during the last session — I was undeniably excited to let an audience hear it, yet there was an inevitable sense of anxiety and self-doubt. I couldn’t have asked for a better group of people to share it with, for everyone was immensely supportive and encouraging. Constructive feedback was provided in a very respectful manner for every participant’s work, and I really enjoyed listening to all the pieces written by my fellow creative minds! I left the workshop not merely with a poem I’m proud of, but with so much more — a better understanding of the different dimensions to gender violence, a stronger mastery of poetry-writing techniques and above all, a group of really kickass feminist friends.

About the Author: Kelvin Ng is a debater by training and part-time poet. His biggest accomplishment is remembering all the lyrics to Beyonce’s ***Flawless — both the original one and the Nicki Minaj remix — so that must mean something.

About the Author: Kelvin Ng is a debater by training and part-time poet. His biggest accomplishment is remembering all the lyrics to Beyonce’s ***Flawless — both the original one and the Nicki Minaj remix — so that must mean something.

I just finished the book ’Shame’, which is about forced marriage, honour killings and domestic violence in the South Asian diaspora of Britain. The author is a Sikh woman from Derby who survived very brutal oppression and violence by her family and community, and has spent her life supporting and advocating for other South Asian women and girls in Britain, mostly of Pakistani origin, who’re affected by the same conditions she was in.

I just finished the book ’Shame’, which is about forced marriage, honour killings and domestic violence in the South Asian diaspora of Britain. The author is a Sikh woman from Derby who survived very brutal oppression and violence by her family and community, and has spent her life supporting and advocating for other South Asian women and girls in Britain, mostly of Pakistani origin, who’re affected by the same conditions she was in.

Disney movies are another good example of gender stereotypes that young children, notably young girls, are exposed to. Cinderella teaches girls that they aren’t worthy of a prince unless they look beautiful, but also have all the domestic skills a women must have. This stereotype is reinforced in Snow White, as Snow stays at home to cook and clean while the dwarves go off to do “the real work.” I wouldn’t be the first person to note how Beauty and the Beast normalizes the existence of domestic abuse and violence within relationships.

Disney movies are another good example of gender stereotypes that young children, notably young girls, are exposed to. Cinderella teaches girls that they aren’t worthy of a prince unless they look beautiful, but also have all the domestic skills a women must have. This stereotype is reinforced in Snow White, as Snow stays at home to cook and clean while the dwarves go off to do “the real work.” I wouldn’t be the first person to note how Beauty and the Beast normalizes the existence of domestic abuse and violence within relationships.