The We Can! team spoke to Norliza Hamidon, a passionate Change Maker and parent to 13 year-old Irfan, on her approach to parenting and engaging her son on gender issues.

By Ashley Tan.

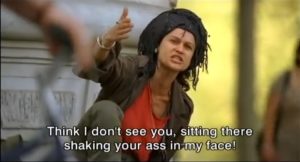

As children grow up in a heavily gendered world, it seems almost unavoidable that their perception of body and self be constantly skewed with unrealistic and unhealthy ideals normalized in popular media. From early on, children are exposed to gender roles, norms and the unequal power men and women have in society. From the toys and clothes that many children are given, to the playmates and extracurricular activities their parents choose for them, children are put in a certain mould based on their assigned gender at birth.

Parenting has one of the most powerful roles to play in the ideas children develop about themselves and the world around them. Conscious, gender-neutral parenting can help children reject damaging notions about gender and instead explore their own individuality. Actively teaching gender equality to children from a young age, demonstrating equal relationships and educating them on gender diversity and consent can go a long way in shaping children’s perspectives.

Parenting has one of the most powerful roles to play in the ideas children develop about themselves and the world around them. Conscious, gender-neutral parenting can help children reject damaging notions about gender and instead explore their own individuality. Actively teaching gender equality to children from a young age, demonstrating equal relationships and educating them on gender diversity and consent can go a long way in shaping children’s perspectives.

Creating a safe space at home where they can ask questions about their body or discuss the messages they come across in the media or outside of the home can also help children form healthy attitudes about gender and become agents of change.

The We Can! team spoke to Norliza Hamidon, a passionate Change Maker and parent to 13 year-old Irfan, on her approach to parenting and engaging her son on gender issues.

“I share with him articles about discrimination faced by women and lead conversations about different gender issues,” she says.

She reminds him particularly of the importance of respecting girls and women, as she is concerned about the prevalent notions of masculinity that teach aggression and trivialise women’s roles and voices.

Norliza thinks parenting can play a crucial role in reducing bullying and overcoming gender stereotypes.

“If adult role models display positive attitudes and actions, such socially-aware behaviour will naturally translate to youth and children,” she says.

Her son, Irfan, 13, recently attended a Youth Change Maker workshop upon his mother’s encouragement. He contributed to our conversation and showed a sensitivity to gender issues and violence that surprised us, for a boy his age.

“Boys don’t always need to be masculine and ‘tough’. Muscles only show that you are physically strong but you might not be mentally or emotionally strong. Boys can also do housework and roles should not be decided by gender.”

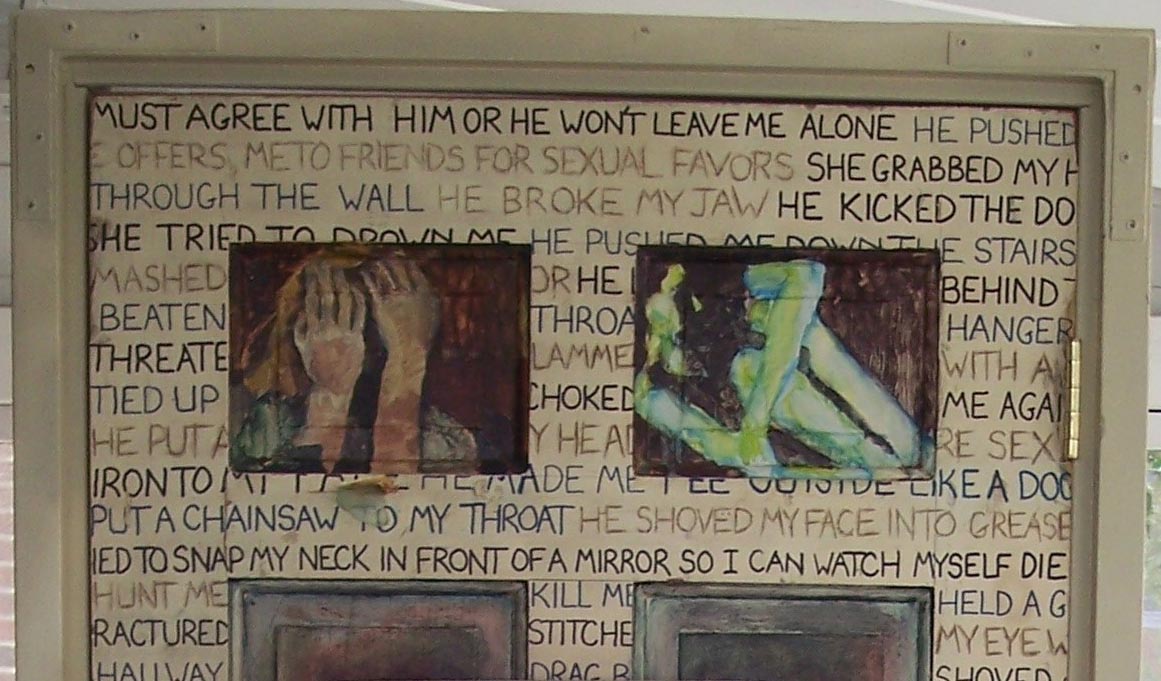

Gender divisions and the disproportionate violence that women and girls face are glaring to Irfan. Still, he has hopes for his generation, and suggests that learning about harmful attitudes early can help eliminate the gender gap.

We were inspired by Norliza’s efforts to show Irfan he can make a difference. She encourages Irfan to stand up for his friends who might be bullied in school and calls him out when he exhibits discriminatory attitudes. She asserts that “it is better to stand up for what is right than be silent.”

Norliza recounts a time when she was disappointed in Irfan for refusing to include a particular girl in his circle of friends because she was “fat”. Through talking about it openly, she managed to get him to see how such behaviour was unfair and hurtful. She probed him to be more accepting of people’s differences, whether in appearance or otherwise.

Norliza notes that it is challenging to ensure children develop healthy, inclusive and gender-equal views because of the many competing influences in society, many of which work to reinforce sexist attitudes and behaviours.

When asked what she would like to see in society, Norliza envisions “a society of men and women respecting each other, working with each other, having equal opportunities, roles and incomes; a violence-free society”.

Norliza and Irfan have each other on their journey towards eliminating prejudice and violence in their own lives and influencing others around them to do the same. They choose to have honest conversations about change rather accepting things as they are.

We hope that sharing their story will encourage other parents and families to think about everyday actions they can take to promote gender equality in the home and outside of it.

If you would like to share your story with us, write to [email protected].

A big thank you to Norliza and Irfan for taking the time to talk to us!